Women of the Asylum

First-Person Accounts of Women Hospitalized in American Psychiatric Institutions 1840 - 1945

Jun 01, 1994

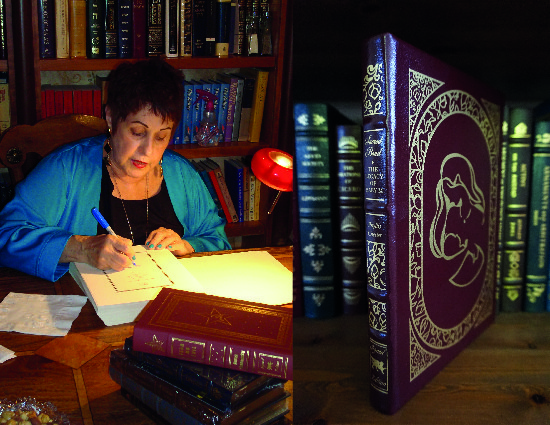

Women of the Asylum: Voices from Behind the Walls, 1840-1945

Written and Edited by

Jeffrey L. Geller and Maxine Harris

Foreword by

Phyllis Chesler

“Women of the Asylum” is a true companion volume to my own Women and Madness, first published in 1972. These 27 first-person accounts are lucid, sometimes brilliant, always heartbreaking, and utterly principled, even heroic. Incredibly, these women were not broken or silenced by their lengthy sojourns in Hell. They bear witness to what was done to them and to those less fortunate than themselves who did not survive the brutal beatings, the near-drownings, the force-feedings, the body-restraints, the long periods in their own filth and in solitary confinement, the absence of kindness or reason—which passed for “treatment.” These historical accounts brought tears to my eyes.

Whether these women of the asylum were entirely sane, or whether they had experienced post-partum or other depressions, heard voices, were “hysterically” paralyzed, or disoriented; whether the women were well-educated and well-to-do, or members of the working poor; whether they had led relatively privileged lives or had been beaten, raped, abandoned, or victimized in other ways; whether the women accepted or could no longer cope with their narrow social roles; whether they had been idle for too long or had worked too hard for too long and were fatigued beyond measure none were treated with any kindness or medical or spiritual expertise.

Elizabeth T. Stone (1842) of Massachusetts describes the mental asylum as “a system that is worse than slavery”; Adriana Brinckle (1857) of Pennsylvania describes the asylum as a “living death,” filled with “shackles,” “darkness,” “handcuffs, straight-jackets, balls and chains, iron rings and...other such relics of barbarism”; Tirzah Shedd (1862) tells us: “This is a wholesale slaughter house...more a place of punishment than a place of cure”; Clarissa Caldwell Lathrop (1880) of New York writes: “We could not read the invisible inscription over the entrance, written in the heart’s blood of the unfortunate inmates, ‘Who enters here must leave all hope behind.’” Female patients were routinely beaten, deprived of sleep, food, exercise, sunlight, and all contact with the outside world, and were sometimes even murdered. Their resistance to physical (and mental) illness was often shattered. Sometimes, the women tried to kill themselves as a way of ending their torture.

I am amazed, and saddened, that I was able to complete my formal education and write Women and Madness without knowing more than a handful of the stories gathered here.

In 1969, 1 helped found the Association for Women in Psychology (AWP). I was a brand-new Ph.D., a psychotherapist-in-training, an Assistant Professor, and a researcher. Inspired by the existence of a visionary and radical grassroots feminist movement, I was conducting a study on women’s experiences as psychiatric and psychotherapeutic patients, and on sex-role stereotyping in psychotherapeutic theory and practice. I planned to present some preliminary findings at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1970, in Miami.

I read psychiatric, psychological, and psychoanalytic texts, and historical, mythological, and fictional accounts of women’s lives. I located the stories of European women who’d been condemned as witches (including Regine Pernoud’s account of Joan of Arc) and, from the sixteenth century on, psychiatrically diagnosed and imprisoned. I read the nineteenth century American heroine, Elizabeth Packard (whose words are contained here), and about some of Freud’s patients, most notably: Anna O (who became the feminist crusader Bertha Pappenheim) and Dora, whose philandering and syphilitic father, in Freud’s words, “had handed [Dora] over to [a] strange man in the interests of his own [extra-marital] love-affair.”

I learned that some well-known and accomplished women, Zelda Fitzgerald, Virginia Woolf, Frances Farmer, Sylvia Plath, and the fictionally named “Ellen West,” had been psychiatrically labeled and hospitalized. Based on numerous statistical, academic, and case studies, and on interviews with female ex-mental and psychotherapy patients, I began to document what patriarchal culture and consciousness had been doing to women for thousands of years, including psychiatrically and “therapeutically,” in the twentieth century in the United States. I was also charting the psychology of human beings in captivity, who, as a caste, did not control the means of production or reproduction and who were routinely abused and shamed sexually, economically, politically, and socially. I was trying to understand what a struggle for freedom might entail, both politically and psychologically, when the colonized group was female.

In the midst of this work, I attended the 1970 APA convention. Instead of delivering an academic paper on behalf of AWP, I asked the assembled APA members for one million dollars “in reparations” for those women who had never been helped by the mental health professions but who had, in fact, been further abused: punitively labeled, ordered to “adjust” to their lives as second and third class citizens and blamed when they failed to do so, overly tranquilized, sexually seduced while in treatment, hospitalized, often against their will, given shock and insulin coma therapy or lobotomies, strait-jacketed both physically and chemically, and used as slave labor in state mental asylums. “Maybe AWP could set up an alternative to a mental hospital with the money,” I suggested, “or a shelter for runaway wives.”

Two thousand of my colleagues were in the audience; they seemed shocked. Many laughed. Loudly. Nervously. Some looked embarrassed, others relieved. Quite obviously, I was “crazy.” Afterwards, someone told me that jokes had been made about my “penis envy.” Friends: this was 1970 not 1870. And I was a colleague, on the platform and at the podium.

Women and Madness was first published in 1972. It was embraced, instantly, by other feminists and by many women in general. However, my analysis of how diagnostic labels were used to stigmatize women and of why more women than men were involved in “careers” as psychiatric patients, was either ignored, treated as a sensation, or sharply criticized by those in positions of power within the professions. My statistics and theories were “wrong,” I had “overstated” my case regarding the institutions of marriage and psychiatry, I’d overly “romanticized” archetypes, especially of the Goddess and Amazon variety. Moreover, I (or my book) was “strident,” “hated men,” and was “too angry.” Like so many feminists before me, I became a “dancing dog” on the “one night stand” feminist academic and professional circuit. Luckily, I was just about to gain tenure at a university; luckily, no father, brother, or husband, wanted to psychiatrically imprison me because my ideas offended them.

It is inconceivable, outrageous, but that is all Elizabeth T. Stone (1842) of Massachusetts and Elizabeth Packard (1860) of Illinois did: express views that angered their brothers or husbands. Phebe B. Davis’s (1865) crime was daring to think for herself in the state of New York. Davis writes: “It is now 21 years since people found out that I was crazy, and all because I could not fall in with every vulgar belief that was fashionable. I could never be led by everything and everybody.” Adeline T.P. Lunt (1871) of Massachusetts notes that within the asylum, “the female patient must cease thinking or uttering any ‘original expression’.” She must “study the art of doffing [her] true character... until you cut yourself to [institutional] pattern, abandon hope.” Spirited protest, or disobedience of any kind, would only result in more grievous punishment.

In her work on behalf of both mental patients and married women, Elizabeth Packard proposes, as her first reform, that “No person shall be regarded or treated as an Insane person, or a Monomaniac, simply for the expression of opinions, no matter how absurd these opinions may appear to others.” Packard was actually trying to enforce the First Amendment on behalf of women! Packard also notes that “It is a crime against human progress to allow Reformers to be treated as Monomaniacs... if the Pioneers of truth are thus liable to lose their personal liberty... who will dare to be true to the inspirations of the divinity within them.” Phebe B. Davis (1865) is more realistic. She writes that “real high souled people are but little appreciated in this world—they are never respected until they have been dead two or three hundred years.”

The talented and well-connected Catharine Beecher (1855) and the feminist writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1886) wanted “help” for their overwhelming fatigue and depression. Beecher, after years of domestic drudgery, and Gilman, after giving birth, found themselves domestically disabled. Gilman couldn’t care for her infant daughter; Beecher could no longer sew, mend, fold, cook, clean, serve, or entertain. Beecher writes: “What [my sex] had been trained to imagine the highest earthly felicity, [domestic life], was but the beginning of care [heartaches], disappointment, and sorrow, and often led to the extremity of mental and physical suffering... there was a terrible decay of female health all over the land.” Nevertheless, both women blamed themselves; neither viewed their symptoms as possibly the only way they could (unconsciously) resist or protest their traditional “feminine” work—or overwork.

Beecher and Gilman described how they weren't helped—or how their various psychiatric cures damaged them even further. In Gilman’s words, Dr. S. Mitchell Weir ordered her to live as domestic a life as possible. Have your child with you all the time. (Be it remarked that if I did but dress the baby it left me shaking and crying—certainly far from a healthy companionship for her, to say nothing of the effect on me.) Lie down an hour after each meal. Have but two hours’ intellectual life a day. And never touch pen, brush or pencil as long as you live.

This regime only made things worse. A desperate Gilman decided to leave her husband and infant to spend the winter with friends. Ironically, she writes, “from the moment the wheels began to turn, the train move, I felt better.”

Adjustment to the “feminine” role was the measure of female morality, mental health, and psychiatric progress. Adeline T.P. Lunt (1871) writes that the patient must “suppress a natural characteristic flow of spirits or talk... [she must] sit in lady-like attire, pretty straight in a chair, with a book or work before [her], ‘inveterate in virtue’, and that this will result in being patted panegyrically on the head, and pronounced ‘better’.” According to Phebe B. Davis (1865), Most of the doctors employed in lunatic asylums do much more to aggravate the disease than they do to cure it.... It is a pity that great men [the asylum doctors] should be susceptible of flattery; for... when there is a real mind, that will flatter no one, then you will see the Doctor’s revengeful feelings all out... [any] patient who will not minister to the self-love of the physicians, must expect to be treated with great severity.... Doctors have been flattered so much they are fond of admiration.

Margaret Starr (1904) of Maryland writes: “I am making an effort to win my dismissal. I am docile; I make efforts to be industrious.”

How did these women of the asylum get into the asylum? The answer is: most often, against their will and without prior notice. Here is what happened. Suddenly, unexpectedly, a perfectly sane (or a troubled) woman would find herself being arrested by a sheriff, removed from her bed at dawn, or “legally kidnapped” on the streets, in broad daylight. Or: her father, brother, or husband might ask her to accompany him to see a friend to help him with a legal matter. Unsuspecting, the woman would find herself before a judge and/or a physician, who certified her “insane” on her husband’s say-so. Often, the woman was not told she was being psychiatrically diagnosed or removed to a mental asylum. Why did this happen?

Battering, drunken husbands had their wives psychiatrically imprisoned as a way of continuing to batter them; husbands also had their wives imprisoned in order to live with or marry other women. Tirzah Shedd (1862) of Illinois writes that There is one married woman [here] who has been imprisoned seven times by her husband, and yet she is intelligent and entirely sane.... When will married women be safe from her husband’s power?

Ada Metcalf (1876) of Illinois writes: It is a very fashionable and easy thing now to make a person out to be insane. If a man tires of his wife, and if befooled after some other woman, it is not a very difficult matter to get her in an institution of this kind. Belladonna and chloroform will give her the appearance of being crazy enough, and after the asylum doors have closed upon her, adieu to the beautiful world and all home associations.

In 1861, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote: Could the dark secrets of those insane asylums be brought to light... we would be shocked to know the countless number of rebellious wives, sisters and daughters that are thus annually sacrificed to false customs and conventionalisms, and barbarous laws made by men for women.

Alice Bingham Russell (1898) of Minnesota was legally kidnapped by a sheriff on her husband’s orders. After obtaining her own release, Russell spent twelve years trying to document and “improve the conditions of the insane.” Russell describes many women whose husbands psychiatrically imprisoned them in order to gain control of their wives’ property. Russell describes a woman who refused to sell her property to suit the caprice of her husband... this young and capable woman who has been doing, up to the very hour before [she was legally kidnapped], all her housework, including the care of two children, leaves a good home and property worth $20,000.00, to become a public charity and mingle and associate continuously with maniacs.

At 32, the unmarried Adriana Brinkle (1857) of Pennsylvania conducted an economic transaction on her own: she sold some furniture she no longer needed. Charges were brought against her for selling furniture for which she had not fully paid. For the crime of embarrassing her father’s view of “family honor,” Brinckle’s physician-father, and his judge friend, sentenced Brinckle to 28 years in a psychiatric hospital. Russell (1898) also tells us of a woman “who had been wronged out of some property [and who was] about to take steps to recover it when she [was] falsely accused and sent to the asylum by fraud.”

Any sign of economic independence or simple human pride in a woman could be used against her, both legally and psychiatrically. Russell describes the following: A woman and her husband quarrel; the wife with independence accepts a position as janitress, hoping her absence will prove her worth at home. She returns to secure some clothing, and learning from a neighbor that a housekeeper is in possession, and being refused admittance, she, in her haste to get justice, takes some of the washing from the clothes line, including some of the husband’s and the housekeeper’s to give evidence of their living together. That evening she is arrested, but has not the least fear but that she can vindicate herself. To her surprise she is without friends or counsel committed to the St. Peter asylum.

Some women of the asylum evolve rather clear-minded views on the subject of marriage and husbands. Like Catharine Beecher, Mrs. L.C. Pennell (1883) of Indiana believed something was truly “wrong” with her (“nervous prostration”), when she could no longer perform her domestic duties. Mrs. Pennell suffered doubly when her family “charged [her] with... feigning insanity to evade the responsibilities of [her] home duties.” Mrs. Pennell’s husband finally had her institutionalized; but he did not visit her for nine months. Of that first visit, Mrs. Pennell writes: Only a moment ago I was feeling so utterly wretched and alone. But my husband had come, and he did care something for me after all. After I had entered the room, and closed the door, he stood looking at me, but not speaking a word until I said, “For heaven’s sake, don’t stand there staring at me in such a manner as that; sit down and say something to me... “Were you insane when you were married?” Not one single, little word of kindness or gesture of tenderness, not the shadow of a greeting, simply this cruel, calculating question. Evidently, he had even then formed the determination that I should never leave that asylum alive.... I answered “I was not insane when we were married.” I have changed my opinion since then, materially, and willingly admit I was insane, and my most pronounced symptom was that I married him.

Some asylum women did not speak; some spoke and made no sense. Some wept incessantly; some were violent. However, most women in asylums did not start out—or even become—insane. According to Adeline T.P. Lunt (1871), A close, careful study and intimacy with these patients (finds no) irregularity, eccentricity, or idiosyncrasy, either in language, deportment, or manner, than might be met with in any society of women thrown together, endeavoring to make the most of life under the most adverse and opposing circumstances.

The women of the asylum feared, correctly, that they might be driven mad by the brutality of the asylum itself, and by their lack of legal rights as women and as prisoners. As Adriana Brinckle (1857-1885) writes: “An insane asylum. A place where insanity is made.” Sophie Olsen (1862) writes: “O, I was so weary, weary; I longed for some Asylum from ‘Lunatic Asylums’!”

According to Mrs. L.C. Pennell (1883), The enforcement of the rules of the institution is the surest way in the world to prevent recovery. And the brutal methods of enforcing such rules call loudly for a law which will secure to insane people the right to a chance for mental preservation.

Jane Hillyer (1919-1923) of--notes that: (Asylum) conditions were so far removed from normal living that they actually aided my sense of cleavage, rather than cleared it up, as they are supposed to do. The few habits of ordinary living that remained with me were broken down by a new and rigidly enforced routine.... My last moorings were cut.

Margaret Isabel Wilson (1931) of says: We had no wholesome activities, no work and no play.... I was afraid of incarceration; I had seen too much of the deadly effects of institutionalization; and I knew that any neurotic subject might break down utterly under the strain...To sum up the effects of my asylum experiences: when I entered I had sufficient money in the bank, some real estate, chattels and personal belongings; a position, a fine constitution, and a fair chance to go on with my teaching. My money was wasted, possessions lost, and friends disappeared; I was left with bad nerves, an impaired constitution, and a weakened heart. Courage remained...I am only one of the many in Blackmoor.

Are these women of the asylum exaggerating or lying? Are they deluded? Obviously not. Each account confirms every other account. Each woman says, quite simply, that she and every other woman she ever met in the asylum were psychologically degraded, indentured as servants, and physically tortured by male doctors and especially by female attendants. At times, these accounts of the asylum are unbearable to read, but if the victims have documented the atrocities for us, I feel obliged to quote them at length.

[1862] Sophie Olsen: The faces of many [women] were frightfully blackened by blows received, partly from each other... but mostly from their [female] attendants.... I have seen the attendant strike and unmercifully beat [women] on the head, with a bunch of heavy keys, which she carried fastened by a cord around her waist: leaving their faces blackened and scarred for weeks. I have seen her twist their arms and cross them behind the back, tie them in that position, and then beat the victim till the other patients would cry out, begging her to desist...I have seen her strike them prostrate to the floor, with great violence, then beat and kick them.

[1865] Phebe B. Davis: There was one very interesting lady who died in one of the water closets... this closet is one of the most loathsome places imaginable; the stench was terrible... [she was] rather tall and thin, and very delicate.... She was rather a troublesome patient, and suicidal, they said. The fact is, that woman had been frightened out of her wits, and then she was literally murdered in that house, for she was worn out by brute-like treatment that I was witness to; I never saw an old canal-horse that was handled more roughly than that lady was when being harnessed down to the bedstead; the girls [attendants] did not know that I saw that.... I thought that she could not live long, and she did not; she was a lady of very delicate sensibilities, and of course her powers of endurance were feeble.... I would advise all who take their friends to the Asylum, to cut their hair very short indeed; it is much better for the patients to have their hair cut off short than to have it pulled out by the roots... there is no prevention against the attendants making halters of the hair of patients.

[1880] Clarissa Caldwell Lathrop: On the floor, on straw mattresses, lay poor, sick, or insane women, chained or strapped by the wrists to the floor, huddled together like sheep... the utter heartlessness of this treatment filled me with indignation and sympathy.

[1898] Alice Bingham Russell: People are sometimes driven insane by treatment and despair in the hospital.... One woman, a Mrs. Murray, was brought to the asylum almost dying of paralysis. They made her walk the floor and beat her to make her dress herself, saying she was stubborn. I protested against such treatment and dressed the woman myself. In the morning she was dead and the doctors called it by some long name.

[1902] Margaret Starr: I found myself [strait-jacketed] and in the room adjoining that of a blind girl.... She announced that she had been in the one room for four years; was not allowed to enter church, nor to take outdoor exercise. She was trying, she said, to save her soul and be reconciled to her imprisonment. That Madam Pike [the female attendant] kept her well dressed but doomed her to live alone....

[1919-1921] Sally Willard: Dr. Reginald Bolls [greeted me] with an airy gesture the sweeping salute of a hand that touched his forehead, curved outward in a wide arc, and dropped smartly to his side. “Physically you’re as sound as a bell... all we have to do is turn our attention to those foolish little foibles and fancies of yours, straighten them out, and send you back home to your good husband again... Dr. Cozzens is a young man with beetling eyebrows and fierce black eyes and a Method. A “personal and individual method of treatment” [sic] based on a “personal and individual theory of human nature” [sic] “Everyone’s been too confounded good to you around here—that’s what’s wrong with you now, and it’s all that’s wrong, too. Everybody’s given in to you, and been s-s-so sorry for you, and wept great hot salt tears over you. How about giving a thought now and then to your husband for instance? Or your father? It wouldn’t hurt you any to wake up to the fact that you’re doing them harm—with your ‘troubles.’ You’ve managed to make them both half sick.”

[1931] Margaret Isabel Wilson: I was like the famous elastic cat—[who] was frozen, burnt, boiled, and poured out of a bung-hole—and then the cat came back!...There was no liberty at all for us. We learned to jump up briskly at the sound of the rising bell, to dress speedily without answering back. I tried to dress as quickly as I could, for I did not wish to be called “fresh”....We could not get a bit of privacy.... Conversation during meals was taboo...

[1943-1950] Frances Farmer: During those [eight] years, I deteriorated into a wild, frightened creature, intent only on survival.... I was raped by orderlies, gnawed on by rats, and poisoned by tainted food.... I was chained in padded cells, strapped into straight jackets, and half drowned in ice baths.... I crawled out mutilated, whimpering, and terribly alone. But I did survive. The three thousand and forty days I spent as an inmate inflicted wounds to my spirit that could never heal.... I learned there is no victory in survival—only grief.... Where I was, wild-eyed patients were made trustees.... Sadists ruled wards. Orderlies raped at will. So did doctors. Many women were given medical care only when abortions were performed. Some of the orderlies pimped and set up prostitution rings within the institution, smuggling men into the outbuildings and supplying them with women. There must be a twisted perversion in having an insane woman, and anything was permitted against them, for it is a common belief that “crazy people” do not know what is happening to them.

Some women of the asylum believe that their inability to function deserved a psychiatric label and a hospital stay. Two of these 27 women feel they were helped in the asylum and afterwards by a private physician. Lenore McCall (1937-1942) of--writes that she recovered because of the insulin coma therapy. She also attributes her recovery to the presence of a nurse, who had “tremendous understanding, unflinching patience [and whose] sole concern was the good of her patient.” After Jane Hillyer (1919-1923) was released from the asylum, she consulted a private doctor who she feels rescued her from ever having to return. Hillyer writes: I knew from the first second that I had made harbor. I dropped all responsibility at his feet.... I need not go another step alone. I perceived at once the penetrating quality of his understanding.... He said afterwards he felt as if he were the Woodsman in the fairy tale who finds the lost Tinker’s daughter in a darkly enchanted forest.... I am sure the necessity of intelligent after-care cannot be sufficiently stressed.... My relief was indescribable. If ever one human being went down into the farthest places of desolation and brought back another soul, lost and struggling, that human being was the Woodsman.

McCall and Hillyer are decidedly in the minority. Twenty-five women of the asylum document that power is invariably abused: that fathers, brothers, husbands, judges, asylum doctors, and asylum attendants will do anything that We, the People, allow them to get away with; and that women’s oppression, both within the family and within state institutions, remained constant for more than a century in the United States. (It exists today still, and in private offices as well as in private and state institutions.)

Do these accounts of institutional brutality and torture mean that mental illness does not exist, that women (or men) in distress don't need “help,” or that recent advances in psycho-pharmacology, or insights gained from the psycho-analytic process, or from our treatment of sexual and domestic violence victims, are invalid or useless? Not at all. What these accounts document is that most women in asylums were not insane; that “help” was not to be found in doctor-headed, attendant-staffed, and state-run patriarchal institutions, either in the nineteenth or in the twentieth centuries; that what we call “madness” can also be caused or exacerbated by injustice and cruelty, within the family, within society, and in asylums; and that personal freedom, radical legal reform, and political struggle are enduringly crucial to individual mental and societal moral health.

These 27 accounts are documents of courage and integrity. The nineteenth-century women of the asylum are morally purposeful, philosophical, often religious. Their frame of reference, and their use of language, is romantic-Christian and Victorian. They write like abolitionists, transcendentalists, suffragists. The twentieth-century women are keen observers of human nature and asylum abuse—but they have no universal frame of reference. They face “madness” and institutional abuse alone, without God, ideology, or each other.

What do these women of the asylum think helped them or would help others in their position? Friends, neighbors, and sons sometimes rescued the women; however, many of the nineteenth-century women obtained their freedom only because laws existed or had recently been passed that empowered men who were not their relatives to judge their cases fairly. Therefore, for them, obtaining and enforcing their legal rights was a priority. Elizabeth Packard (1860) became a well-known and effective crusader for the rights of married women and mental patients; Mrs. L.C. Pennell (1883) also suggested reforms, as did Mrs. H.C. McMullen (1894-1897) of Minnesota who, while imprisoned, wrote some model Laws for the Protection of the Insane. As noted, Alice Bingham Russell (1898) documented the stories of still-imprisoned women and helped them obtain their freedom. Mrs. Pennell (1883) for example, proposed that: Every doctor, after being called to examine a person for insanity shall immediately notify the proper authorities; that all persons confined in any asylum... be allowed to sleep; that the excessive habit of using opium, tobacco, or intoxicating liquors, shall disqualify any man for Superintendent, or a subordinate position in any hospital.

Mrs. McMullen proposed that All rules and laws for the protection of the hospital inmates should be posted up and enforced. It would be a relief of mind to know what rights they can demand.... Those who work should be allowed compensation for it.... Patients shall have the right to correspond with whom they please.... Letters written by patients shall be by them dropped into a letter box.... Friends shall be allowed to see patients.... All new attendants should be over thirty years of age.... It is unjust to compel elderly people to submit to the judgment of the young and giddy.

In addition to legal reform, and the liberty to leave an abusive husband or an abusive asylum, what else proved helpful, or invaluable, to the women of the asylum? Phebe B. Davis (1865) writes that “Kindness has been my only medicine”; Kate Lee (1902) of Illinois proposes that “Houses of Peace” be created, where women could learn a trade and save their money, after which they could “both be allowed and required to leave.” Lee suggests that such “Houses of Peace” “operate as a home-finder and employment bureau...thus giving each inmate a new start in life [which] in many cases [will] entirely remove the symptoms of insanity.” Margaret Isabel Wilson (1931) of says that “Nature was her doctor.” Leaving the asylum helped Wilson. She writes: “It took me months to get over the effects of my incarceration.... Through companionship, my appetite came back; I could sleep in peace, and there was nobody to annoy me. There were no maniacal shrieks to make me shudder; no attendants to yell out orders; no nurses to give me arsenic and physics; no doctors to terrify me... the things [I] sorely missed while institutionalized: (1) liberty; (2) my vote; (3) privacy; (4) normal companionship; (5) personal letters and uncensored answers; (6) useful occupation; (7) play; (8) contacts with intelligent minds; (9) pictures, scenery, books, good conversation; (10) appetizing food.

I’d like Phebe B. Davis (1865) to have the last word about why women become “excitable” and about why psychiatric hospitalization is an especially painful and outrageous form of punishment. Davis writes: I find that active nervous temperaments that are full of thought and intellect want full scope to dispose of their energy, for if not they will become extremely excitable. Such a mind cannot bear a tight place, and that is one great reason why women are much more excitable than men, for their minds are more active; but they must be kept in a nut-shell because they are women.