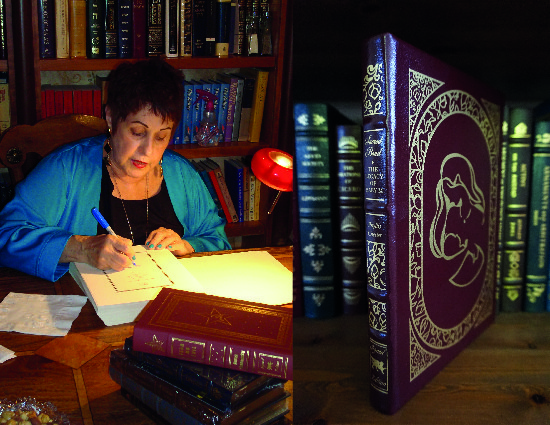

With Child

A Diary of Motherhood

Nov 15, 1979

What does a 37 year old celebrated feminist do when she becomes pregnant? She writes a book about what pregnancy, childbirth and mothering taught her – as woman, wife, mother and daughter.

Chesler's book "With Child" combines the "ordinary" thoughts and fears of expectant mothers with the "not-so-common" concerns of a successful career woman. We see her at the child-care shelf at the local bookstore, musing, "I am every woman who has dared to hope that despite everything, a child will sweeten her days, soften the blow of loneliness and old age. I am every woman who has ever honored her mother by becoming a mother. You are my emissary to the next century. You, child, are my life offering to all the mothers who have preceded me." But we also see her adrift in a world where her peers either are childless and professionals or mother who have postponed success and now envy the success of others. Chesler asks, "is every woman over 35 without a child asking herself whether or not to have a child now? Is every mother of teen-agers asking herself what to do about her life now that the children are grown?"

Chesler candidly admits her four previous abortions – she could have been the mother of children aged 18, 16, 14 and/or 7. We also learn about the author's impressions of Israel's women and Greece's current state – since she visited both during her pregnancy. We are privy to an afternoon visit Margaret Mead paid Chesler – significantly, Mead became a mother at 38, Chesler at 37. Although the author's experiences and impressions are disjointed and erratic they somehow manage to convey perfectly the schizoid feelings that pregnancy sometimes brings. Not all women feel as Chesler did but some – like this reviewer – will not their head and remember all to well the separateness and excitement that accompanied a first-time pregnancy.

Physical discomforts and changes are chronicled with rueful resignation. Yes, we hear about swollen ankles, stretch marks, a 60-pound weight gain, lower back pain, and the trauma of the author's 31-hour labor. When it's all over, she writes: "Will I ever sit again…I'm sore. Throw away the textbooks! I think I've discovered the secret of maternal personality. After you give birth you never shit again. You don't dare to. And you never tell anyone why you keep smiling so mysteriously."

Settling down in a small apartment in Manhattan with an infant and an unemployed student husband soon becomes more taxing than Chesler expected Good child care is hard to find; her husband agrees to be the mother, Chesler agrees to be the wage earner, and still there are problems – not enough sleep, money, time, intimacy, or solitude to write. Aware on the one hand that her problems are the problems of women everywhere, but also conscious that she is more fortunate than many women she concedes: "I'm afraid of being called selfish (for complaining), stupid (for wanting to say home – or for having to leave home to earn money), really stupid (for having expected to be spared this problem), incompetent (for not being able to solve this dilemma), a 'trivializer' (of the romance of motherhood), a "whiner' (about what every other mother takes for granted, knew about all along, handles magnificently, without complaint, smiling)."

Chesler's involvement with her husband drastically changes. He begins to emerge as a platonic child-care support system when the romance between them is obliterated by exhaustion, money problems, jealousy over baby Ariel's care, and Chesler's book promotion and lecture tours. Ariel begins to be the "romance" in her life and there is precious little time for him; she and David repeatedly fall into bed and succumb to sleep not as lovers but as brother and sister, or, better yet, as mere survivors. Although there are several interesting conversations in the book with other women – mostly mothers – the most appealing feature, for me, was the reconciliation between Chesler and her own mother. Years of resentment and jealousy and misunderstanding were put into perspective by Ariel's arrival. Perhaps Chesler was able to see the love she felt for her child as a continuation of the love her mother felt for her – whatever the cause, it is endearing, an easily identifiable part of the book for any woman who has struggled to build a better relationship with her own mother. By the time Ariel reaches his first birthday Chesler admits that she is closer to her mother than at any other time in her entire life.

The book includes some harrowing narratives about women who have lost custody of their children to unscrupulous monied husbands and there are also some rather nasty scenes when David remind the author that he knows how to mother better than she does. At the root of everything, of course, is Chesler's need to write, to be, "Phyllis not to be obliterated by motherhood. She writes Ariel, "I hate your father. I love your father. If he consults me one more time about your diaper rash while I'm working I may kill your father."

Although this "diary" can easily be read in a couple of hours, Chesler's observations will cling and resurface days, weeks later. There is something intriguing about the current crop of feminist-oriented women writers – Erica Jong and Nora Ephron to name few – who have decided to become mothers in their late 30s. Perhaps, as one friend told Chesler, they've heard the new warning: "A child is worth it. Husbands come and go. They're not really there for you, if you know what I mean. But a child! If you're there now for a child, that child is always there for you."