When Valerie Solanas Shot Andy Warhol: A Feminist Tale of Madness and Revolution

May 22, 2020

Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence

Valerie was on a military mission. She moved like a shot, nothing slowed her down. She had only one thing to say, and she’d say it with a gun. She carried her pistol in a paper bag. Valerie looked awkward, menacing, like a street person, a wino, or a maniac, she had too much energy and too much self-absorption for a woman.

Valerie exited the elevator on the sixth floor of 33 Union Square West, Andy Warhol’s Factory, where underlings stretched canvases, ordered the silkscreens, swabbed on the paint and mass-produced the same image over and over again: Marilyn Times Twenty, Jackie in Blue, Jackie in Gold, Double Elvis. Masterful insect vision, and a capital concept. Warhol used everything, and everyone; he was celebrated for doing this. People threw themselves at him, to be used and discarded “by Warhol,” as if this was his true art form, and they his true subjects. Well, Valerie had had enough.

Solanas wrote:

“She’d seen the whole show—every bit of it—the fucking scene, the sucking scene, the dyke scene—(she’d) covered the whole waterfront, been under every docks and pier—the peter pier, the pussy pier… you’ve got to go through a lot of sex to get anti-sex… funky, dirty, low-down, (she) gets around… (she’s) been through it all, and (she’s) now ready for a new show; (she) wants to crawl out from under the dock.”

Valerie had played the part of a lesbian in one of Andy’s films but he’d never paid her. He’d promised to produce her screenplay but he’d lied. Then, behind her back, without telling her, The Master of Indifference had obtained the movie rights to the Manifesto, she’d written. She no longer had any right to her own work: he did. Valerie didn’t want Andy to make the movie. He’d have her played by a transvestite, he’d use her, just like he used everyone. It would amuse him.

Great Men always degraded Great Women. They didn’t even bother to learn their names, they just called them baby, chick, bitch, cunt, woman. Or they gave them fake names: Candy Darling, Ingrid Superstar. Warhol was a voyeur, all-see ing, all-hidden, untouchable. Valerie was fed up with how Warhol enjoyed watch ing other people have sex, overdose, kill themselves.

What about that Great Seducer, Auguste Rodin? He’d used Camille Claudel, and then he’d thrown her away. Claudel sculpted Rodin’s pieces, but Rodin got all the money and all the credit. Rodin the Thief became immortal. Claudel the Great was destroyed in her lifetime, and then forgotten. The art world didn’t take Claudel seriously: she was only Rodin’s mistress, not his equal. Claudel’s own mother and her brother, the poet Paul Claudel, despised her. To them, she was a crazy slut. Claudel’s brain broke beneath the injustice; her family had her locked up in a loony bin for, what was it, thirty years? Claudel pleaded to be set free, but her heartless, provincial mother told the doctors, “My daughter has all the vices, I don’t want to see her again.” Camille should have made her getaway to Cuba. Someone really should ax Rodin’s work or inscribe Claudel’s name on all the plaques.

What about The Great F. Scott Fitzgerald? Without Zelda, Scott would have been much, much less; he grew stronger as she grew weaker, until she had to go to the loony bin, too. They locked Zelda up for twenty years, and then they burned her to death in a loony bin fire. At least you had to kill Zelda to stop her.

No one had to pull the trigger on Marilyn Monroe, she was already programmed to self-destruct. What a waste. The Blonde Blowup Dolls should always make them pay. Mae West did. Peroxided women are supposed to spend the rest of their Anglo-Saxon lives lounging and laughing on the way to the bank. Intensely Intellectual Individuals, like Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, were something else, but they, too, ended up killing themselves. Virginia was a godamm genius trapped in the body of a wife: she should have traveled in a caravan of Great Women to Italy. Plath had too much housework to do, and no time to write. Plath should have killed her husband or the kids and made her getaway. Maybe to Mexico or Paris, lots of expatriates there. As Valerie saw it, it was a geographic problem; Woolf and Plath were living in England, they needed to get out, it was too damp, it rained too much.

I ought to destroy Andy’s work, just bust up the place, Valerie thought. In 1914, British suffragist Mary Richardson swung an ax at Diego Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus. London society and the art world shit their drawers! C’mon, guys, Richardson was only trying to say: See how it feels to have something you value mutilated and destroyed?

Valerie disapproved of Richardson’s action. Fuck the property-as-symbol, she thought. That’s for Daddy’s Girls. How do I get rid of the idea of The Great Man? I get rid of one, I destroy one Great Pretender: that’s how I stop the idea.

Otherwise, the Great Men just carry on—oh how they carry on, carried by their landladies, bankers, students, wives, mistresses, faggot lovers, and assorted boot lickers. They go on and on, even after they die. Everyone keeps singing their praises, no one gives a shit for The Great Women. Great Women can’t carry on, because no one carries them. They don’t have an entourage who’d put up with their eccentricities, cultivate their reputations, merchandise their work, and fuck them on demand. They don’t have husbands (or wives), (or friends), who’d sell their bodies and keep the kiddies quiet so The Great Woman can paint, and they don’t have glittering High Society hostesses vying for their company. Great Women end up in loony bins and nursing homes. Some even end up married-with-kids in the suburbs. No one ever remembers them.

Women’s photographs don’t even make the obituary page! Check it out, asshole. This makes perfect sense. Women are not allowed to live, so they never get to die. Women’s little deaths aren’t important. Easy come, easy go. Hey, you’d think they’d reward the “nice girls,” give them a big photo on the obit page: “Mom of Four Dies, Baked Cherry Pies,” but no. Why should they? Men can get away with any thing they do to women, because men are not physically afraid of women. It’s as simple as that.

Valerie and Andy both came out of Nowheresville, USA, but she was still a white girl, and white girls didn’t build empires; they competed with a vengeance to be sold to the highest bidder; they won Miss Nude America and marriage contests, one by one, each against every other contestant, no team work at all. Valerie was on her own. Andy had a gang.

Warhol was big, and getting bigger: Warhol was really “happening.” Warhol and his entourage were producing, marketing, publicizing, acquiring stocks, bonds, real estate, jewelry, antiques, furniture, clothing, artwork, and a world-class reputation. Warhol’s images were easy, familiar; you didn’t need a course in abstract expressionist art in order to understand them. Warhol was fun—and a good investment too. Warhol gave us ourselves and our gods. Commodities: giant Brillo boxes, Coca-Cola bottles, Campbell soup cans, all in bright, blaring colors. Fame: Jackie and Marilyn and Liz, the girl with the ultra violet eyes. Violence: cartoon blowups of JFK assassinated, and Marilyn Monroe shot dead—not the real Marilyn, but six of Andy’s silkscreens of Marilyn, which Dorothy Podber, a performance artist, had shot at with real bullets, long before Valerie came on the scene. Andy retitled them: “Shot Through Marilyns.”

By 1988, Andy Warhol’s work would be auctioned off for more than $1 million apiece. In 1989, his 1964 painting of Marilyn Monroe with a bullet hole above one eyebrow, would sell for $4.1 million. By 1992, Warhol’s Diaries would sell for $1.2 million and his magazine, Interview, would sell for $12 million. Warhol’s personal effects would be auctioned off for $25 million. Warhol’s estate would be formally devalued at $220 million dollars; some estimates would run as high as $600 million.

Valerie was unknown, a lesbian ex-prostitute, a street person, a “crazy,” a feminist writer. She was a loner; she didn’t like other women. She didn’t want to join a group, plan an action, march, or sue anyone. Things were personal, not political, this was between her and Andy, and her patience for bullshit had run out. It wasn’t enough for Valerie to say: “The Emperor is naked,” and it wasn’t enough for her to be known as the first woman to say so. Valerie wanted to take the Emperor of Exploitation out, she wanted to enact her own analysis, she wanted to get rid of Warhol, not just talk about it. Scary stuff. The stuff that History is made of, the stuff that gets you into a padded cell or into the electric chair.

Sometime in 1967, Valerie had written a 42-page pamphlet which she’d called: The Manifesto of the Society for Cutting Up Men: The SCUM Manifesto (1968). The Manifesto was electrifying, brilliant, crackpot. Any housewife could see that what she was saying was true. But, Valerie contradicted herself, she was too weird, she was dead-wrong—nah, she was crystal clear, a crazy bitch, and terrifying. Valerie wanted women to kill men and take over the world.

“SCUM is impatient: Those females who are given to slamming those who unduly irritate them in the teeth, who’d sink a shiv into a man’s chest as soon as look at him, if they knew they could get away with it are SCUM. A small handful of SCUM could take over the country within a year, (or) within a few weeks by systematically fucking up the system, selectively de- stroying property. (It was time) to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex… SCUM will kill all men who are not in the Auxiliary of SCUM.”

Who the hell was she? Was Valerie some kind of feminist Black Panther? Was she a performance artist? No one knew. Valerie spent most of her time at the Chelsea Hotel, and at Warhol’s Factory, not demonstrating against sexist beauty pageants or petitioning for equal pay. Valerie sold copies of her Manifesto on the streets. She earned enough for cigarettes and sandwiches. She was always broke. Finally, one day (that’s when everything always happens: on a perfectly ordinary day), Valerie was evicted. She stood outside the Chelsea Hotel, right there, next to her mattress, and books, and two shopping bags filled with clothes. It had finally happened, she was a Bag Lady.

And then the Devil, aka Maurice, came out of the hotel. He knew Valerie, he’d read her Manifesto: she’d been pestering him to publish it. The stuff’s psychotic, he’d thought, but daring, and kinky. On the spot he offered Valerie exactly what he’d offered Terry Southern for Candy and Vladimir Nabokov for Lolita: $500, just sign on the dotted line. Valerie signed. She needed the money. Desperately, man. Maurice was now entitled to the hardcover, paperback, and movie rights to Valerie’s little bombshell of a book—and he had the rights to her future books, too. The next day, in a moment of idle merriment, Maurice sold Andy Warhol the movie rights to Valerie’s Manifesto.

She’d signed; she’d sold something priceless: the farm, her virginity, her only child, her soul, and for very little money. She’d needed the money, she’d taken it, but did that entitle them to treat her like a whore or a field hand? (Actually, Andy’s crowd treated heirs and heiresses the same way. On this score, they were indiffer ent to social class.) Valerie knew the kind of sick movie Warhol was capable of making. Andy could also refuse to make the movie—and refuse to sell the rights to anyone else. Smug little faggot-bastard.

Valerie wanted her rights back. Actually, all her rights. She wanted money, she wanted to star in the movie of her life. Only she could explain her ideas on the Johnny Carson show. She wanted the Daily News to publish the SCUM Manifesto. Valerie made the rounds, she talked to agents, lawyers, author’s representatives. They all agreed: the contract was scandalous, even awful, but, she’d signed, it was perfectly legal, there was nothing she could do. A deal was a deal; heads, I win, tails, you lose.

So: It was a showdown between Valerie and all the Great Men who thought that women were only pussy, born to serve, disposable, easy to flush down the toilet, there’s more where that came from. Well, no more Great Men. No more Muzak. No more nice girls. It was a showdown between Solanas and Warhol, between Amazon archetype rising and Patriarchy.

Valerie was on a military mission. Jael slew Sisera, Judith cut off Holofernes’ head, and Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol five times in the chest at point-blank range. Valerie wounded Andy in the esophagus, lungs, stomach, liver, and spleen. POP, you’re dead! Daddy, I’m through, through with the black heart of you. This is the winter of our discontent, the autumn of our Patriarch. The actress Viva mistook the loud sounds for “a whip cracking.” Factory member and actor, Taylor Mead, said: “If she hadn’t shot him, I would have.”

Ultra Violet: “Why were you the one to get shot?” Andy Warhol: “I was in the wrong place at the right time.”

Twenty-three years later, in Balcon, an art publication, journalist Laura Cottingham would write: “No other man suffered violence under the rhetoric of radical feminism. That Warhol was an artist, ‘the’ artist of post-war America, locates Sol anas’ feminist assault within the short tradition of feminist attacks on art of which Solanas’s is the only documented post-war incident. Even if Solanas’s behavior before and after the shooting, especially her repeated instances of paranoia, is best described as ‘crazy,’ that judgement doesn’t necessarily invalidate the clarity of her motive.”

Solanas had no escape plans. Either she hadn’t read her own Manifesto, or she didn’t think it applied to her. Solanas wandered out, down, and into Times Square, where women with tasseled tits danced naked on all fours, and in cages. Home. Within a few hours, Solanas turned herself in. She informed the police: “It’s not often that I shoot somebody. I didn’t do it for nothing. I shot him because he had too much control of my life.” She also advised them to: “Read my Manifesto, it will tell you who I am.”

Would George Washington, John Brown, Toussaint L’Overture, Mother Jones, Emma Goldman, Kate O’Hare, David Ben Gurion, Mao-Tse Tung, Agnes Smedley, Golda Meir, Fidel Castro, Nelson Mandela, Bobby Sands, or Yasir Arafat have turned themselves in? Was Solanas a political terrorist—or was she just plain crazy? Two feminists immediately visited Valerie in jail.

“Valerie, we’re here to stand by you. We’d like to help you if we can,” says NOW leader Ti-Grace Atkinson, purposefully. Ti-Grace is our feminist Scarlett: an ex-bride from Louisiana, blonde and willowy, who, once-upon-a-time, probably knew how to flatter a man to death with the best of them—but Tara’s gone now, she’s got only herself to rely on, and she’s pure southern steel.

Valerie snorts. “Stand by me, my ass. You don’t want to help me. You just want to get famous off of what I did. You’re just a privileged, well-educated Daddy’s girl. I’ve already written you off in my Manifesto. I can’t talk to you.”

Solanas wrote:

(Your) niceness, politeness, ‘dignity,’ and self-absorption are hardly conducive to intensity and wit, qualities a conversation must have to be worthy of the name… only completely self-confident, arrogant, outgoing, proud, tough-minded females are capable of intense, bitchy, witty conversation.

“Hey, baby, you’ve done a hell of a thing for a white girl. And we’re with you. Don’t blow it for yourself. You’re lucky that Andy’s not dead, the motha’s gonna live.” So says Flo Kennedy, Ti-Grace’s black sister-in-arms. Flo is our Tina Turner, unstoppable, extravagant; she’s a lawyer, but looks and sounds like a rock singer, or a comedienne, in all her “rings and political button things,” her cowboy hat and stomping boots.

“Oh, you’re a riot, Alice,” snarls Valerie, channeling Jackie Gleason. “You want to go on television as a way of controlling me because you’re too chickenshit to become me. I’m the real thing. A cool killer, out to fuck up the system. You two make me sick.”

“Valerie,” Ti-Grace, here. “This is very, very serious. We have a lot of work to do. Drop the attitude, and let’s get down to it. You’re facing years of jail time. Years—and without our help, no one will understand what you did, what it means.”

“Listen to me, you blonde bitch. I invented the feminist movement. Me—not you. And I won’t share the credit with you, or with your marches in broad daylight, or with your good-girl idea about civil disobedience: going limp for Daddy. Have you ever destroyed private property? Have you ever killed anyone?”

Thus, spake Solanas.

SCUM will not picket, demonstrate, mark or strike to attempt to achieve its ends. Such tactics are for nice, genteel ladies who scrupulously take only such action as is guaranteed to be ineffective… SCUM will always remain on a criminal as opposed to civil disobedience basis—that is, opposed to openly violating the law and going to jail in order to draw attention to an injustice. Such tactics acknowledge the rightness of the overall system and are used only to modify it slightly… SCUM is out to destroy the system, not attain certain rights within it.

“That’s a real wide welcome mat you’re extending.” That’s Flo, sizing up what she’s up against. “Listen Buster: you haven’t killed anyone yet either. So: you’ve been up against it, but darlin’, so have we all. Talk nice to your sisters. We’re all you’ve got.”

“I have no sisters.” Valerie laughs. “They all died in the war while you were at a meeting. I don’t need sisters, I operate alone. I had no choice, no woman like me ever does. I had to stop him. I’m already overthrowing the system.”

Flo and Ti-Grace saw that Solanas was crafty, crazy, apolitical, maybe even a fascist. But their analysis of what she’d done was political. They had no choice either: they had to work with what they had.

So they say: “Okay, Valerie Try us. What have you got to lose? What do you want?”

“Can you break me out of jail? I’d like to go to Venezuela. Can you smuggle in a gun? Look: Can you make sure they won’t have me declared insane? I’m not crazy. You wouldn’t be here if you thought I was.”

Flo tried, but nothing she said persuaded anyone that Valerie didn’t belong on a psychiatric ward. Warhol refused to press charges. Twenty-three days later, Sol anas was indicted for attempted murder, assault, and illegal possession of a fire arm. Solanas pled to first degree assault. She was sentenced to three years for “reckless assault with intent to harm.”

After Valerie was released, she began to accuse feminists of stealing her ideas. She wrote to feminist newspapers, Off Our Backs and Majority Report, and said so. Acknowledgement wasn’t what she was after: she didn’t want to share her ideas with others—especially with people who said they agreed with you, but who didn’t do anything. Valerie was quite canny, but her concreteness was maddening—it was the stuff of madness.

But look: Every godamm woman in America was on a diet—except the whitemiddleclass feminists, who weren’t even on day-long protest hunger strikes. The feminists-in-charge weren’t chaining themselves to fences, stockpiling weapons, or destroying private property on behalf of their revolution. They were seizing or gasms, not state power; and they sure as hell weren’t killing any rapists. No, as Valerie saw it, they were busy dressing-for-success at the office and being glamorous on television. After an interview or a demonstration, they avidly searched for their names and faces in the media-mirror on the wall, a fatal attraction, their version of Kilroy was here.

The feminists-in-charge were trying to convince everyone, themselves most of all, that feminism was nothing to be afraid of, that actually, they were feminists because they wanted to help men. They were no risk, no pain, all gain, kind of feminists; they cared about what to wear when you’re being fired, five easy steps to the gas chamber. Valerie hated them. She wrote:

The conflict is not between females and males, but between SCUM—dom- inant, secure, self-confident, nasty, violent, selfish, independent, proud, thrill-seeking, free-wheeling, arrogant females, who consider themselves fit to rule the universe… and nice passive, ‘cultivated,’ polite, dignified, de- pendent, scared, mindless, insecure, approval-seeking Daddy’s Girls… Sex is the refuge of the mindless. And the more mindless the woman, the more deeply embedded in the male ‘culture,’ in short, the nicer she is, the more sexual she is. The nicest women in our ‘society’ are raving sex maniacs.

Women felt cheated. Valerie did too. Women were in a rage. So was Valerie. The feminists-who-were-not-in-charge were very, very angry. Daughter Dearests.

If a woman didn’t have “the right stuff,” that proved that someone: another woman, must have stolen it from her. Thus, women were entitled to steal in self defense. Stealing was okay, men stole from women all the time, it’s how they got things done. Feminists stole things from each other all the time: and they lied about what they were doing, mainly to themselves. Any woman who was not dead yet was fair game; any woman who’d accomplished anything at all, however minor, was the immediate enemy target, to be isolated, scorched, destroyed.

Feminists said that all women were equal—but only if the women who had “more,” gave it all back to those who had “less.” If not, there’d be no revolution. Funny, feminists preached a good line about men, but they wouldn’t practice tak ing anything back from them; they’d only target-practice on women. Feminists also said that feminist ideas belonged to feminist groups, not to individuals. Feminist groups wanted Great Women to give up their ideas, or apologize for having any. Feminists sometimes called this “sisterhood.”

Maybe Valerie was crazy, but she was crazy as a fox. She saw right through the Chinese Cultural Revolution in feminist America—and refused to have anything to do with it. By 1980, she’d disappeared from New York altogether.

Rumor had it that she was really Shulie Firestone, and that she was still living in New York, only “underground.” Some said that she’d moved to Portland or Phoenix.

Valerie had always wanted Andy to make her a star. And he did, he did. Without Warhol—without what she did to Warhol, Solanas would have been a famous-for fifteen-minutes-flash-in-the-pan. Which is why fame and the horrified anonymity of the fame-crazed masses is so combustible and dangerous a mix. We shoot our stars. To become them. And so Solanas’s one bold, weird, deed lived on: real, always still happening.

In 1972, in Women and Madness, I discussed Solanas’s actions in political terms. In the mid-1970s, in New York City, the “It’s Alright to Be a Woman Theatre” performed a play about Solanas; and publisher Nancy Boreman reprinted her Manifesto in Majority Report.

In 1983, in Britain, The Matriarchy Study group republished the SCUM Manifesto. They wrote: “We have made every effort for two years to contact Valerie Solanas, but have not been able to do so. We would welcome her contacting us or information as to where she is. This publication is nonprofit making. Royalties for sales are being set aside for Valerie Solanas. If these are not claimed the money will be used to promote her ideas.”

Women, including feminists, are not usually this respectful of each other. Were the Matriarchists afraid Solanas might shoot them if they didn’t acknowledge her properly? Did Solanas actually teach them manners, Clint Eastwood style, through the barrel of a gun?

On February 22, 1987, Andy Warhol died, mysteriously, of heart failure, after being left unattended in a hospital after routine gallbladder surgery. On April 25, 1988, Valerie Solanas died, of pneumonia, in San Francisco, that queen of a city.

I fall into step beside Valerie. She is wearing dark glasses and walking very fast in Chelsea. I can barely keep up with her.

“Valerie, wait up for me,” I say. “Do you still think women should shoot men?”

“Stop following me,” she snarls. “Why don’t you just shoot someone of your own?” But later, over coffee, she says: “Look, I wrote it all down for you. How slow can you be? If you want to get rid of the Great Male Pretenders, you need millions of women to go out on strike, thousands of women to screw up the system. Sugar in their gas tanks, crossed nuclear wires, jammed telephones at the White House, free merchandise. When I was around, there was nothing but ‘all mouth, no do.’ You need women who can keep their mouths shut. But mostly, you need killers, they’re the elite.”

Ah, Valerie, the white women I know, myself included, are all well-dressed weaklings; we find it hard to take ourselves seriously. We’ve been too carefully taught to prefer being hit to having to hit. We’d rather die than kill—even in self defense. Worse, some of us are convinced that our inability to defend ourselves physically somehow constitutes a free choice, a moral virtue, a political philosophy. And thus, we cover our enormous nakedness.

Only someone who lives in her body, who occupies it fully, who knows how to fight—but refuses to do so—can freely choose to practice pacifist politics. That’s not us. We’re possessed, colonized. They’ve chased most of us right out of our bodies, we’re nothing but bodies: but “we’re” not in there anymore, we’re elsewhere, in a fog, in a fugue state, disassociated: Hitler’s Housekeepers, Stalin’s Sweeties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

[text]

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

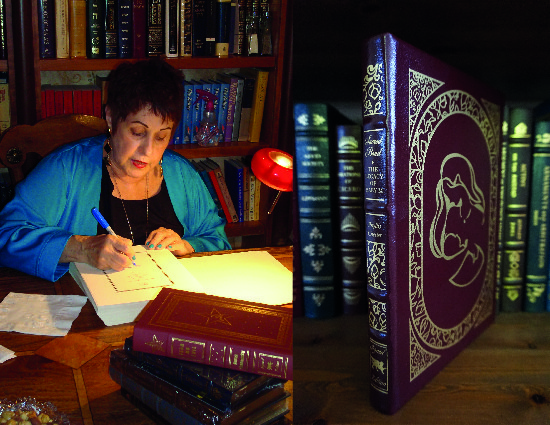

Phyllis Chesler, Ph.D, is an Emerita Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies at City University of New York. She is a best-selling author, a feminist leader, a retired psychotherapist and an expert courtroom witness. Dr. Chesler is a co-founder of the Association for Women in Psychology (1969), The National Women's Health Network (1974), and The International Committee for the (Original) Women of the Wall (1989).

Dr. Chesler was an early 1970s abolitionist theorist and activist: She wrote about and delivered speeches which opposed rape, incest. pornography, sex and reproductive prostitution, and sex trafficking. She organized and/or participated in demonstrations outside the movie Snuff; outside Dorian’s Red Hand to protest the murder of Jennifer Levin by Robert Chambers after a night of drinking there; organized repeated demonstrations outside the Hackensack, New Jersey courthouse where the Baby M hearings were underway and outside the surrogacy pimp Noel Keane’s NYC clinic; outside the courthouse when Joel Steinberg was sentenced for the murder of Lisa Steinberg; and in numerous ways that concerned the trial of Aileen Carol Wuornos for which she assembled a team of expert witnesses which were never called upon.

She is the author of eighteen books, including the feminist classic Women and Madness, as well as many other notable books including With Child: A Diary of Motherhood; Mothers on Trial: The Battle for Children and Custody; Sacred Bond: The Legacy of Baby M; Woman's Inhumanity to Woman; and Women of the Wall: Claiming Sacred Ground at Judaism's Holy Site. After publishing The New Anti-Semitism (2003), she published The Death of Feminism: What's Next in the Struggle For Women's Freedom (2005) and An American Bride in Kabul (2013), which won a National Jewish Book Award. In 2016, she published Living History: On the Front Lines for Israel and the Jews 2003-2015, in 2017 she published Islamic Gender Apartheid: Exposing A Veiled War Against Women, and in 2018, she published A Family Conspiracy: Honor Killings, and a Memoir: A Politically Incorrect Feminist.

Dr. Chesler has published four studies about honor-based violence, focusing on honor killing, and penned a position paper on why the West should ban the burqa; these studies have all appeared in Middle East Quarterly. Based on her studies, she has submitted affidavits for Muslim and ex-Muslim women who are seeking asylum or citizenship based on their credible belief that their families will honor kill them. She has archived most of her articles at her website: www.phyllis-chesler.com She is working on a book about the Aileen Wuornos case.

RECOMMENDED CITATION

Chesler, Phyllis. (2020). When Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol: A feminist tale of madness and revolution. Dignity: A Journal of Sexual Exploitation and Violence. Vol. 5, Issue 1, Article 2. http://doi.org/10.23860/dignity.2020.05.01.02 Available at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol5/iss1/2

REFERENCES

Solanas, Valerie. (1968). The SCUM manifesto. UK: Phoenix Press. Available at http://ccs.neu.edu/home/shivers/rants/scum.htm

Download the full article here.