Shabbat Metzora Shalom

Apr 08, 2022

The Iconoclast at New English Review

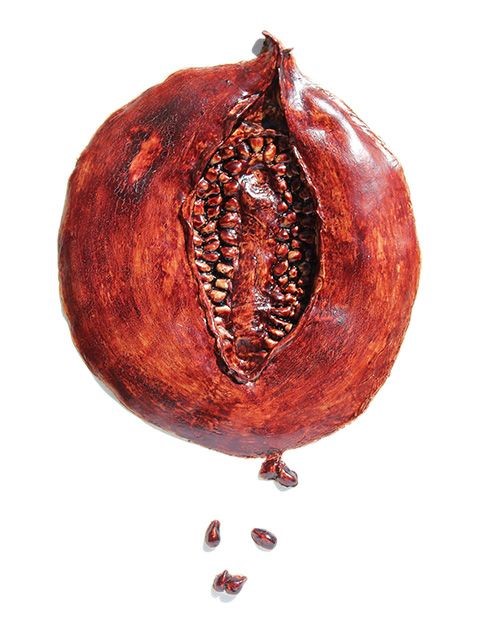

I dedicate this Shabbat d’var to all those Jewish women who were made to feel ashamed of their bodies and who were taught to consider menstruation a Curse.

I was in Hebrew School when I menstruated for the first time. I thought I was dying and that my mother would surely kill me and so I ran home, expecting the worse and indeed I found it. Reader: She slapped me. No comfort in that. No useful explanation either. To this day, I’ve never understood this custom—but now, I see its possible source partly in parasha Metzora, and more universally, in human psychology.

The rabbis have taught us that tzora’as in both chapters Tazria and Metzoro (14:1) is not really leprosy but is, rather, a moral and ethical disease, perhaps related to lashon ha’ra. It is not a natural or biological occurrence and a priest is required to diagnose and help cure, via atonement, what is believed to be a human failing. However, after covering various male bodily discharges, we suddenly read this: “When a woman has a discharge and the discharge will be blood in her body” (‘V’eesha ke tihiyeh zavah dam zovah b’besara” (15:19), she is also considered impure, must self-segregate while she is menstruating and thereafter, for another seven days, after which she must bring a sacrifice to atone for her “impurity.”

What is going on? Menses are natural and have nothing to do with committing an “impure” ethical act. Why is menstruation treated as if it is a disease? Without menstruation there can be no childbirth. True, blood is being shed and the patriarchal gaze is transfixed—what strange and dangerous Medusa-magic is this? My teacher, Dr. Freud, viewed this extreme psychological revulsion and terror as related to the Oedipus Complex and to a boy’s fear of castration. I viewed this alleged castration fear as a “cover” for male uterus envy and said so in 1978, in my book About Men. What do you think those male-only Begats are telling us?

In Engendering Judaism: An Inclusive Theology and Ethics, Rachel Adler quotes Cynthia Ozick who, in “Notes on Finding the Right Question,” asked: “Where is the Commandment that will say from the beginning of history until now, “Thou shalt not lessen the humanity of women?” Ozick called for a “new Yavne.”

Devorah Zlochower in “Establishing and Uprooting Menstruation With the Pill” (in Jewish Legal Writings By Women, edited by Micah D. Halpern and Chana Safrai), addresses the way in which the birth control pill challenges, if not completely upends, the rules concerning menstrual impurity.

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin also questions the prohibition against not allowing a woman to touch, read from, or dance with a Torah on Simchat Torah “given the nature of her susceptibility to ritual impurity… (but) a Torah scroll is not susceptible to ritual impurity.” He favors upholding minhag but notes that one may even change the law if doing so “leads to a positive act” not to a sin. R. Riskin notes that even the Talmudic sages “tell us to be sensitive to changing times and circumstances.”

I offer the last word to Ellen Frankel in The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman’s Commentary on the Torah. Frankel, writing as a fictionalized Beruriah the Scholar says: “… All the other ‘discharges’ that require various degrees of quarantine and purification are either voluntary (sexual intercourse), episodic (childbirth, nocturnal emissions), or abnormal (leprosy, infection, blood discharges at times outside a woman’s menstrual cycle.) But menstruation is the only condition that’s ongoing, predictable, and a sign of bodily health. To include this normal physical function with other discharges is to define all healthy women as ritually impure for half of all the days during their fertile years.”

Mommy darling z”l: Now do you understand?