Review of Andrea Dworkin's Mercy

Aug 31, 1991

By Phyllis Chesler

Andrea Dworkin is, without question, a great writer, a writer's writer: as "masterful" as Miller or Mailer -- even Joyce; as passionate as Fanon, as gentle and as world-weary as Baldwin; as much a troubadour on the literary high road as Whitman or Ginsburg or Kerouac--only more so; philosophical--no, far more philosophical than either Camus or Sartre; raw and rough and cynical and fierce, really fierce, like Genet or Celine; pitiless, utterly without mercy, as she challenges God on His lack of "mercy" (the book's title is from a passage in "Isaiah"); bitter, wry, shocking, like Baudelaire or Rimbaud, when they were new in the world; patient, thorough, graphically accurate, like De Beauvoir, Eliot, Lessing; brave, heartbreakingly brave, like Leduc or even Levi--except the truth is, Dworkin really has no predecessor; I only wanted to put her in her place, where she belongs.

Reading MERCY is more like reading something the prophet Cassandra turned military tactician might have written--had she managed to escape His-story as well as Agamemnon, to become an "avenging angel," the kind of Joan of Arc who leads women (an "army of raped ghosts"), not men, into visionary and heroic battle.("We surge through the sex dungeons where our kind are kept, the butcher shops where our kind are sold; we break them loose; Amnesty International will not help us; so at night, ghosts, we convene; to spread justice...They don't stop themselves, do they?...(We must) stop them...One day the women will burn down Times Square; I've seen it in my mind; I know; it's in flames. The women will come out of their houses from all over and they will riot and they will burn it down, raze it to the ground, it will be bare cement; and we will execute the pimps. No woman will ever be hurt there again; ever; it is a simple fact...If I won the Nobel Prize and walked to the corner for milk (my name) would still be cunt...It's like as if nigger was a term of endearment, not just used in lynching and insult but whispered in lovemaking").

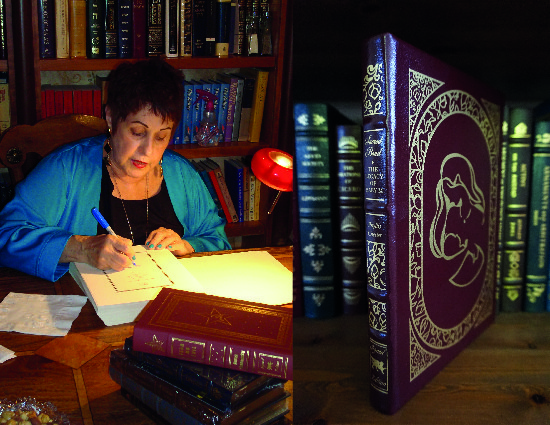

Dworkin's second novel, MERCY, has just been published in America by Four Walls, Eight Windows, more than a year after the book first appeared in England. It is a literary tour de force that, until now, no American publisher, feminist or otherwise, was willing to publish. AMERICAN PSYCHO, yes, and for huge sums of money; Dworkin's superb novels, no.

Something is wrong, obscenely wrong here and it's what MERCY is all about. However, MERCY is not "about" something. Like all great novels, MERCY (its experimental and compelling use of language), is greater than the sum of its parts. For example, we would not ask of Doestoevski's CRIME AND PUNISHMENT or, for that matter, of Richard Wright's NATIVE SON: "But what's his point? Is he saying murder is justified?"

Dworkin's MERCY is not about women killing men; it's about the far more pervasive phenomenon of men killing women: psychologically, sexually, physically and of getting away with it--and about women, including feminists, supporting their right to do so. (Two such feminist voices brilliantly and painfully begin and end the book). MERCY is about stopping the violence against women, about figuring out how to do so especially since most women, like Dworkin's narrator, would literally rather be killed than to kill in self-defense, "don't really believe in hurting...anyone...can't stand to think about using (the knife), what it would be like, or going to jail for hurting him, I never wanted to kill anybody, and I'd do almost anything not to."

The book is part automythography, part meditation, part prose-poem; it's range of subjects include sexual violence and political freedom, human courage and resistance, and, of course, female sexual pleasure: the book is sexually and non-pornographically "hot" and being female, Jewish, American, and politically active in the second half of the twentieth century, after Auschwitz, after the Atom bomb. ("I was born in 1946 in Camden, New Jersey, down the street from Walt Whitman's house, Mickle Street, but my true point of origin, where I came into existence as a sentient being, is Birkenau, sometimes called Auschwitz II or the Women's camp, where we died, my family and I, I don't know what year").

Dworkin's MERCY is the first book ever to take us inside the experience of serial sexual abuse. She gathers all the missing pieces together, everything we educated/ sexually "liberated"/ knew-the-world-could-end/ girls never understood when it was first happening and can't remember since ("No one remembers the worse things...Anything I can say isn't the worst; I don't remember the worst. It's the only thing God did right in everything I seen on earth: made the mind like scorched earth. The mind shows you mercy"). Dworkin shows us what it's like--exactly--to be molested at nine in a darkened neighborhood movie theatre, or at home, by our Daddies, from infancy on, or by the boys we ourselves were crazy about in grade and high school and college, or on the streets or at parties or in marriage or in the American and European peace or anti-war or anti-fascist movements: what our confusion about our own bodies and boundaries meant, given that no one: our own parents as well as the century's best poets, novelists, philosophers, ever talked about it. ("I liked books and I would have enjoyed a cup of coffee with Camus in my younger days, at a cafe in Paris...(but) no philosopher could afford to ignore incest or, as I would have it, the story of man, and remain credible"); given that we ourselves were never sure that "something" (rape) had really happened or that if it did, that we didn't "want" or hadn't "provoked" or somehow didn't enjoy it. Dworkin writes about what such violence means in the lives of girls and women and about what it does to us. ("Years later there are small suicides, a long, desperate series of small suicides...if you're adult before they rape you there you've got all the luck; all the luck there is. The infants; are haunted; by familiar rapists; someone close; someone known; but who; and there's the disquieting certainty that one loves him; loves him. There are these women--such fine women--such beautiful women--smart women, fine women, quiet, compassionate women--and they want to die; all their lives they have wanted to die; death would solve it; numb the pain that comes from somewhere"0.

Someone, Marlene Gorris, perhaps, who directed the widely acclaimed films A QUESTION OF SILENCE and BROKEN MIRRORS, should be lured by Hollywood to turn MERCY into a film. It's THELMA AND LOUISE for real--only they've just joined forces with Barbara Streisand's incest-survivor prostitute in NUTS, on trial for killing John in self-defense, Linda Hamilton's military hero in TERMINATOR TWO: JUDGEMENT DAY, who's trying to save the world, Jody Foster's FBI agent in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS, who's trying to stop a serial killer of women, the battered housewives in SLEEPING WITH THE ENEMY, THE BURNING BED, MORTAL THOUGHTS, DEFENSELESS, etc.