Reflections On Kate Millett, 1934 to 2017

Kate Millett Memorial Service

Oct 01, 2020

KATE, YOU TOOK YOUR LAST BREATH ON EARTH in the city you loved most: Paris, the city which once welcomed expatriates Gertrude, Alice, Pablo, Ernest, and Sir James of Dublin, and where the early morning aroma of fresh bread was reason enough for you to rise too.

I finally understood you in historical context when I read Andrea Weiss's Paris Was a Woman: Portraits From the Left Bank. Then, I recognized your culture, one in which sophisticated and talented lesbians took many lovers, competed against each other for sexual favors, slept with their lover's lovers, and everyone either became life-long friends or abandoned each other or the group entirely.

Just as you belonged to so many cities, just so, you also had so many different “selves.” You were many different Kates.

You were Kate, the highly ceremonial hostess, offering your guests wine as if it were a libation to the Gods, floating little candlelit paper boats out on the lake at the Farm for the Japanese holiday of Obon; and you were also Kate the raging Mad Queen; Kate the bully; Kate the victim; Kate the unbearably humble; Kate the in creasingly all-too-silent.

You were the most cosmopolitan, the most continental, the most European identified of our feminist intellectuals; well, Andrea (Dworkin) was too. You believed that ideas matter and that intellectuals must lay their bodies down for the sake of “Revolution.”

You were also the Kate who could easily pass for a homeless person, out on the Bowery in blustery winter weather, trying to sell your farm-grown Christmas trees. (Oh, how chapped your hands were, how red were your cheeks).

You were Kate the sharecropper farmer, who, like Gerald and Scarlet O'Hara in Gone With the Wind, were adamant that owning land is everything and that land must be kept at all costs. You drove a tractor, cut wood, stood on dangerously high ladders to get at a failing roof.

Do you remember the time I visited one weekend when I was on a hard-and-fast deadline and you demanded that I put my shoulder to the wheel of your Sheltered Workshop (I sometimes viewed the Farm in just this way, as your personal alternative to a loony bin)? “C'mon Chesler,” you growled, “just get on the goddam ladder and help me do this.”

I was horrified. Terrified. Flabbergasted. But you would not let go of me until I at least planted a Victory Garden of flowers by your side.

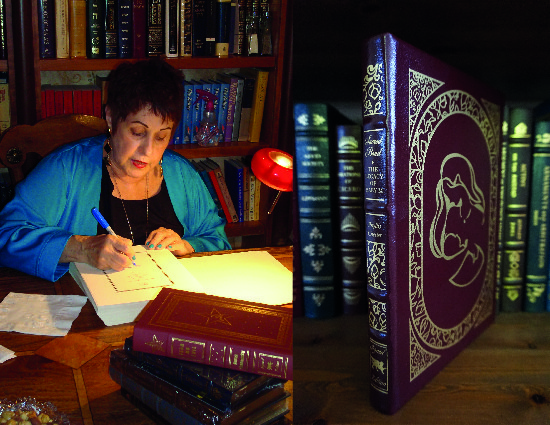

But even as Kate-the-Farmer, you still sometimes drank your morning coffee in a French ceramic bowl, always made little toasts at dinner, and were, at all times, surrounded by books and bookshelves.

Your Sexual Politics (1970) was, perhaps, the most influential and the most “famous” of the Second Wave feminist books--although we all stood on the shoulders of those brilliant articles and demonstrations that preceded us. That same year, Shulie [Shulamith Firestone] published her equally amazing The Dialectic of Sex.

In Flying, (1974--I loved that book), you captured the energy of the early days of breakneck activism, as well as the unexpected cruelty among feminists, and you also described what it was like to experience fame as something of a human sacrifice.

You were prescient about the ways in which some of the same women who were inspired by your work would turn on you because you were “famous” and some thing of a genius--and they were not; the ways in which some women used you, even cannibalized your fame for their own gain. I saw it all, I missed nothing, but

I also saw how, in your own way, you exacted your due in this particular Devil's bargain.

Ah Katie: You were tireless, relentless, in “trolling the dark side” on behalf of women's freedom, and you did so doggedly, even during the dark days, the dog days, the days of despair.

In The Basement: Meditations on a Human Sacrifice (1979), you more than equaled Truman Capote and Norman Mailer, in your non-fiction novel about the physical and sexual torture-murder of a sixteen-year old girl, Sylvia Likens, in Indianapolis, at the hands of the ringleader, a middle aged woman named Gertrude Baniszewski, her teenaged daughter and son, and some neighborhood children. They tortured Sylvia most horribly for weeks and then carved “I’m a prostitute and proud of it” into Sylvia’s skin. The details are unbearable. How did you bear it? Did you?

When your Basement art installation opened, there she was, a life-sized Sylvia on the floor; when I realized that she was wearing your clothing and a wig styled to resemble your hair, I was shocked, slightly sickened.

In Going to Iran (1982), you truly grasped the misogynistic nature of an Islamic theocratic regime that would go on to murder its best and its brightest.

In The Looney Bin Trip, (1990), you described being locked up for “mental illness” (or, as you would have it, for your political beliefs), and the terrible toll such imprisonment took upon you, how offended your dignity was, and how bouts of solitary confinement in the Bin were, for you, literally torture, given that you were claustrophobic.

Even I had a hard time with The Politics of Cruelty: An Essay on the Literature of Political Imprisonment (1994) but I soldiered on, fearing that your graphic depiction of state-administered torture had either become a dangerous obsession—or was your way of controlling your terror about it.

By 2010, there we were: two women of a certain age, bent over by spinal stenosis and numerous surgeries, often hanging on to our walkers, but still Talking the Talk.

Katie: I want to thank you for your generosity, for always trying to include me, and for suggesting that others do so too. You introduced me to extraordinary women: Lesbian activist and author, Sydney Abbott, Architect Phyllis Birkby, musician Joan Casamo, philosopher Linda Clarke, academic Maria del Drago, painter and author Buffie Johnson, lesbian rights activist and authorS Barbara Love, photographers Sophie Kier and Cynthia MacAdams, novelist Alma Rautsong/Isabel Miller, sculptor Alida Walsh. And all the Farm women.

As you know, some of these women became very dear to me.

It was a privilege to be your friend. I will never forget you.

Despite everything, despite anything, I wouldn't have missed this revolution, not for love or money. I remain forever loyal to that moment in time, that collective awakening which set me free from my former life as a “girl.” Allow me to paraphrase Shakespeare’s King Henry the Fifth’s most memorable speech:

(She) that outlives this day, and comes safe home, Then will she strip her sleeve and show her scars. And say “These wounds I had.. This story shall the good (woman) teach her children; From this day to the ending of the world, But we in it shall be remember'd; We few, we happy few, we band of (sisters); For (s)he to-day that sheds (her) blood with me Shall be my sister; be she ne'er so vile, This day shall gentle (her) condition; And (gentlewomen) everywhere now-a-bed Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here, And hold their (humanity) cheap whiles any speaks That fought with us…

(My paraphrasing of Shakespeare is part of forthcoming book titled A Politically Incorrect Feminist.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Phyllis Chesler is an emerita professor of psychology at the City University of New York. She is a feminist scholar and writer. https://phyllis-chesler.com/

RECOMMENDED CITATION

Chesler, Phyllis. (2020). Reflections on Kate Millett, 1934 to 2017: Kate Millett Memorial Service. Dignity: A Journal of Sexual Exploitation and Violence. Vol. 5, Issue 2, Article 13. https:/doi.org/10.23860/dignity.2020.05.02.13 Available at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol5/iss2/13.