Mother-Hatred and Mother-Blaming

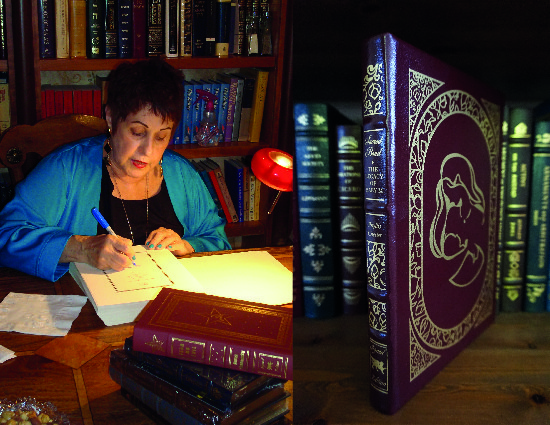

What Electra Did to Clytemnestra

Apr 15, 1990

Motherhood: A Feminist Perspective

By Phyllis Chelser

Clytemnestra is a queen and the mother of three children: Iphegenia, Electra and Orestes. She is also the wife of Agamemnon and the sister of Helen (better known as Helen of Troy), who marries Agamemnon's brother Menelaus. As Homer's Iliad tells us, Helen runs off with Paris of Troy. The two brothers (Agamemnon and Menelaus), mount an expedition to win Helen back and to punish Paris for seducing her. For more than a decade, these patriarchal warriors lay siege to Troy (perhaps a matriarchal civilization). Agamemnon tricks Clytemnestra into sending their daughter Iphegenia to "visit him"--ostensibly to betroth her to a great prince; in truth, her father intends to--and does kill her as a ritual sacrifice in order to win the war. Agamemnon captures and destroys Troy, kills or enslaves the people and sets sail for home. He brings his slave-mistress Cassandra (the Trojan visionary and princess) back home with him.

His long-abandoned queen, Clytemnestra, stabs Agamemnon to death for having killed their daughter Iphegenia; in turn, Clytemnestra's son Orestes, and her daughter Electra, conspire to kill her for having murdered their father. Ultimately Orestes is exonerated by the goddess Athena who decides that husband-murder is a more serious crime than mother-killing or matricide.

Aeschylus has immortalized this tragedy of the house of Atreus in The Oresteia which consists of three plays: Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides.

We are all Electra; certainly, we are all Electra's daughters. We, and out mothers before us, have all conspired in Clytemnestra's murder. We have all committed matricide. We are therefore all mistrustful of our own daughters. (Will they one day conspire against us?)

We symbolically kill our mothers--and our daughters--every day; daily we commit sororicide. We are not conscious of what we do; when challenged, we deny it. ("I didn't do it"; "I wasn't there"; "She did it first"; "I don't remember any of this"; "My back was to the wall," etc.)

Electra only "conspires" in her mother's murder; her brother, Orestes, acts directly. Orestes commits matricide and is haunted and pursued by the (female) Furies. Orestes demands a public reckoning, a jury, exoneration.

Electra kills her mother indirectly; she spurs Orestes on to action but her own hands are "clean." The furies do not pursue Electra. But why not? Is Electra unaware, amnesiac about her role in her mother's murder? Electra's suffering, in private, is unknown.

Electra has her side of the story. She feels spurned and shamed by Clytemnestra. For Iphigenia, Clytemnestra was willing to kill her husband; for Electra, she cannot even keep up royal, patriarchal appearances. Electra is ashamed to be the daughter of a woman who is "loathed as she deserves; my love for a pitilessly slaughtered sister turns to (Orestes)." In Electra's eyes, Clytemnestra cares more for her lover-consort Aegisthus than for her two remaining blood-children.

Electra is jealous of Clytemnestra's involvement with Aegisthus, a mere "boyfriend." Perhaps Electra is furious that because of her mother, she, Electra, is no longer respectable or marriageable in patriarchal terms. Electra addresses her murdered father Agamemnon:

We have been sold and go as wanderers because our mother bought herself a man. Now I am what a slave is, and Orestes lives outcast with his great properties while they go proud in the high style and luxury of what you worked to win...grant that I be more temperate of heart than my mother, that I act with purer hand.'

Indeed, how is it that Clytemnestra is so attached to one blood-daughter, Iphegenia, but not to her other blood-daughter, Electra? Something is already amiss. Electra is no Persephone or "Kore" to her mother; Clytemnestra is no Demeter or mother goddess, nor is she living in a matriarchy. Is this what infuriates Electra--even more than her father's murder? Is Electra outraged because she, her mother's heiress, is being dishonoured--and all for the sake of a mere man, a boyfriend? In terms of earlier matriarchal and/or goddess worshipping cultures, Clytemnestra's lover Aegisthus could easily have been a son-consort. As such, his existence would never demean or shame (matriarchal) family honor.

What is amiss between Electra and Clytemnestra is what they represent: the Fall. They live after goddess-0murder or matricide has been committed, after daughters and mothers have already lost each other, after daughters have come to worship fathers and brothers more than mothers or sisters. As I wrote in Women and Madness, and in About Men, since that Fall, matricide, female infanticide and sororicide are daily psychological occurrences among the daughters of Man.

Patriarchy is literally about the male legal ownership of children. (We carry our father's names.) It is about how we as women, learn to expect less from men, but to trust and like men more than we trust or like other women, including our mothers, from whom we expect everything and whom we do not forgive for failing us, even slightly.

It's important to remember that most mothers in the patriarchy are, in Mary Daly's words, their daughter's "token torturers," whose job it is to break each girl's will, to bind the feet of her mind, so that she may serve Him on earth. Mothers--no longer Mother-Goddesses--also hope to keep their daughters at home with them forever: as their truest love, their step child, servant, scapegoat. Daughters are not meant to wander off too far away or to shine too brightly. Mothers dop not nurture daughters to slay their fathers or their husbands or the male state--not even symbolically, for the sake of woman's honor or freedom.

Patriarchy is also about women not viewing or experiencing maternity or motherhood as an existentially or politically transcendent experience. For example, in 1977, and again in 1979, most publishers whom I approached with the idea for With Child: A Diary of Motherhood and for Mothers on Trial: The Battle for Children and Custody were "not interested." Men, women, and feminists in publishing all told me that motherhood had been "done." I asked by whom: Homer, Virgil, Dante, Cervantes, Shakespeare? Emphatically, they told me that women were not interested in hearing about pregnancy, childbirth or newborn motherhood; that they were more interested in equal pay for equal work; and that anyway, it was fathers, not mothers, who were custodially oppressed.

Many feminists (both heterosexual and lesbian, mothers and not-mothers) are strongly ambivalent about female biology, pregnancy, and childbirth; as if our own biology rather than patriarchy is persecuting us. I encountered strong hostility to the very fact of biological motherhood when I was involved in the Baby M custody battle. I write about such female, feminist attitudes in Sacred Bond: The Legacy of Baby M (1988).

In 1980, when I first started interviewing women about difficulties, conflict, betrayals suffered at the hands of other women, I discovered that, like Electra, women find it hard to recall the pain they have caused another woman. Women (especially feminists) were also very worried about the kind of research I was doing. One woman told me that "some of her best friends are women"; another said that since she "had a very good relationship with her mother that what I was saying couldn't be true"; a third said that "men will use this against us so you'd better not publish anything"; a fourth asked "Are you going to name names?" ("Name names? I'd probably have to name every woman who ever existed," I replied.)

We are all Electra, and we are also Clytemnestra. We do not remember conspiring psychologically in matricide; or in female infanticide. As feminists, we only spoke of ourselves as "sisters," as if our biological sisters or "best girl friends" in grade school had actually been "sisterly" in feminist or political terms. But what ever happened to our mothers? Despite the feminist emphasis on female role-models, were we feminists entirely without mothers? Did we need to reject our mothers as too patriarchal? Did we need to keep quiet about this? Is there any connection between this and the "difficulty" (envy, competitiveness, ambivalence, fear) that so many women have with female leadership and achievement both within themselves and in others?

I am the mother of a biological son; I have no such biological relation to a daughter. As a feminist theoretician and activist, I do have a relationship to "daughters." Often, painfully, it is like Clytemnestra's relation to Electra. I write about this briefly in Dale Spender's excellent book, For the Record: The Making and Meaning of Feminist Knowledge (1985). I wrote this in response to Spender's essay on my first book, Women and Madness (1972).

Over the years, I (along with nearly every other feminist intellectual) have been pained and mystified to find how little of my theory-making or work is mentioned (agreed or disagreed with) in the works of other feminists, especially academics; and in the works of other feminists, especially anti-academics. So many feminists (like mothers? like daughters?) feel unnamed, forgotten, unappreciated, not fully credited by those whose lives and works we have envisioned, influenced, hoped for. (Is our hunger, our egotism, our need for support bottomless? Are we insatiable? Do we expect too much? Or too much from the "wrong" people?)

Why do feminists (like other ideologues) recognize our intellectual foremothers so selectively? Why recognize personal friends--but not 'enemies' or competitors? Why write women we don't "like" out of our history even as we are making it? Why is it easier for feminists to remember a dead foremother rather than a living one; a 'minor' rather than a 'major' one? Why such amnesia--if not in the service of psychological matricide?

If Franz Fanon (1963, 1965) and James Baldwin (1956, 1963) could write about color-prejudice among colonized Blacks; if Albert Memmi (1971, 1973) and Primo Levi (1986) could write about anti-semitism among Jews; then how can I not describe woman-hating among women? Would women, especially feminist psychologists and therapists, have any problem understanding that women have internalized patriarchal woman-hatred? That women are not necessarily "sisterly" within the male--dominated family; or outside the home, situated in different social classes, races, religions, etc.

Women, after all, marry and comfort the very men who wage war against other women (and men); women cook their food, prop them up. Women deny that they are complicit, refuse to acknowledge it, afterwards say that they "didn't know" what was going on--perhaps just as good Germans once said they "didn't know" what was going on....

Both women and men--that means me and you--have an easier time blaming Mommy, than blaming Daddy; have a much harder time engaging in symbolic father-murder (patricide) or brother-murder, than in mother-murder, daughter-murder or sister-murder. Like Electra, we too forget what we've said and done; and we're not necessarily haunted by the Furies afterwards. We underestimate our power to wound, paralyze, destroy another woman. I want to share some selections from my work in progress on this subject. Begun in 1980, it's a melancholy meditation entitled Woman's Inhumanity to Woman. I begin with letters from an archetypal patriarchal mother to an archetypal patriarchal daughter.

A MOTHER ADDRESSES HER DAUGHTER

Oh Daughter! It is bitter to be the Mother of daughters, it is far easier with sons. Your smiles were all for your father, none for me who bore you. When you couldn't wind me around your finger, you had no use for me. Your smile terrified me. I knew you didn't mean it. For me you only had contempt. You thought that any woman who was as unhappy as I was had only herself to blame.

You wanted. You didn't want. You acted as if it was up to you. Where did you get such an idea from? Surely not from me. I told your father that if I didn't knock some sense into you you'd never get to have sons of your own. Who would protect you if not me? I did for you what my mother did for me.

You thought me a monster, a stepmother, a witch. You hated me. You wished me dead. You denounced me, you denounced me. You hated my life, yet you imagined yourself in my place. How could I trust you with any truths? You'd only run with them to your father for a trinket or two. The two of you thought me too old-fashioned, too bitter, a nag, a fool, every one's workhorse, not to be honored or obeyed, or helped. Definitely not worthy of love.

Oh Daughter mine! I tried to wash my hands of you but I couldn't. You were my flesh and blood. I never stopped trying to teach you; you never learned a thing. Whenever you got into trouble you blamed me, not your laughing father. You wanted to remain his laughing girl and you expected me to clean up your mess. What else did I have to do anyway? And when I did, you despised me as much as when I refused to. You still saved all your smiles for men, for strangers.

A DAUGHTER ADDRESSES HER MOTHER

Oh Mother, was it tenderness that drove you to prefer your sons, your "prettier" daughters, your most light-skinned children to me? Tenderness that had you pull my hair, slap my face, call me bad names, tell me I had only myself to blame, tell me that I was bad and that you were washing your hands of the whole mess?

Oh Mother, was it tenderness that drove you to order me about as if my very presence filled you with disgust? Tenderness that made you angry at my budding breasts, drove you to bind my feet, cut out my clitoris, flatten all my flesh, order me t keep my eyes lowered, my hair and all my smiles hidden?

Oh Mother, was it tender to tell me nothing of what was to come and what it meant: about marriage, motherhood, death? Tender not to whisper to me even once about resistance or escape, about honor and freedom.

Oh Mother! And when my husband beat me and left me for his mistress, when I and my children were huddled together on the floor, cold and hungry, where were you? Did you arrive with kisses, a pot of soup, a shawl, an offer that I return home with you? "You made your bed, now lie in it" you said and also "Your father never left me! You must have done something to provoke that man--now undo it if you know what's good for you" and "You can't come and live with us, the house is too crowded, my health isn't what it once was, I have responsibilities toward your brothers' children." My mess was my own you said, I had created it, not you. You weren't about to wash my behind for me, you'd washed your hands of me long ago.

UNTITLED

A mother yells at her daughter. Her face grows huge, red. Her voice--as sharp and as flat as a knife--balloons out of control until it has her daughter completely surrounded.

"Who do you think you are?"

"How dare you?"

"Are you mocking me? Don't you ever talk to me in that tone of voice or I'll kill you myself with my bare hands. I'll show you what it is to talk back you ugly fat lazy dumb idiot..."

The Medusa Head shows herself to women only. Only a daughter carries the memory of Her corrosive green fury. Not only has she lost Her mother's love: she is also about to be killed. Her mother won't save her: how can she? Her mother and her murderer are one and the same.

Is this where we learn to misjudge or at least to withstand emotional abuse from men? Do we think that men are like our mothers, that they really lobe us, that their rage will "blow over," that we are not really being injured?

Do we so fear becoming as impotent, as tyrannical as our mothers that we are willing to rush headlong into the arms of the male tyrants, readied for them by our mothers, but feeling sufficiently safe with them because at least they are not women? Ah, but this flight into the arms of the Godfather is also how we vindicate our mothers. Our usefulness to tyranny, our refusal to rebel, is proof of our mother's ability to tame a human being into utter servility.

This is also the only way we are allowed to keep our mothers with us forever: hidden inside our own characters, alike like two peas in a pod, twins or sisters, ageless, eternal, never-changing.

Does male fury also comfort us by reminding us of our mothers, of paradise lost and gone wild, jungled, snaked, a place suddenly too dangerous for us as women to roam in unaccompanied by men.

UNTITLED

What have they done to use? What have we done to ourselves? Each woman knows that if she sides with another woman against a man or against men's laws that "the men" will come for her, in broad daylight and in utter darkness, knows that they can hand-cuff, interrogate, rape, imprison her, knows that she might grow slowly mad and be forgotten.

A woman is brave when she knows what can be done to her but, despite such knowledge, helps other women anyway. A woman is brave because she chooses to withstand terror. A woman is as brave as she is willing to do combat with the "good little girl" within, the voice that tells her not to help, you'll get in trouble, you'll get caught, you'll be sorry, the grownups will punish you, they'll make you cry, no one will like you....

Every woman (me too), has already been branded. We are unnaturally vulnerable to humiliation and threats of punishment.

But other women are only as safe as I am brave. I am only as safe as other women are brave.

Women are safe only if we are all brave.