Marcia Rimland’s Deadly Dilemma

Sep 19, 1993

For more than 5,000 years, no mother anywhere has ever been legally and automatically entitled to custody of her own child. Only men have been entitled to sole custody of children. Women have been obliged to bear and rear children—who carry their father’s last name, without which they are considered illegitimate.

Although most custodial parents in North America and everywhere else are mothers, this does not mean that women always “win” custody; rather, mothers retain custody only when fathers choose not to fight for it. In 62 countries surveyed world-wide, fathers were legally and automatically entitled to custody if they wanted custody—whether or not they fulfilled their paternal obligations.

Mothers were obligated to care for and support their children without any reciprocal rights; most rose to the occasion heroically. Nevertheless, women had few rights as individuals and no rights as mothers over and against the rights that men have over women, that husbands have over wives, that fathers have over mothers, and that states have over citizens. In general, mothers everywhere are vulnerable to legalized father right—whether that right is embodied by a legal or genetic father, paternal family or tribe, or by the state, acting as a surrogate father.

In the last 15 to 20 years, when American fathers fought for custody they increasingly won custody, from 63% to 70% of the time, whether or not they were previously absent, distant, parentally non-involved, or violent (Chesler, 1986; Pascowicz, 1982; Polikiff, 1982, 1983; Takas, 1987; Weitzman, 1985). Similar trends have been documented in

Canada (Lahey, 1989) and in Australia, France, Holland, Great Britain, Ireland, Norway, and Sweden (Chesler, 1991; Smart and Sevenhuijsen, 1989). Fathers do not win because mothers are unfit, or because fathers have been participatory parents, but because mothers are expected to meet more stringent standards of parenting. This double standard has also been documented by ten 1989-90 U.S. State Supreme Court reports on “Gender Bias in the Courts” which confirm that there is one set of expectations for mothers and another less demanding set for fathers.

Today more and more mothers, as well as the leadership of the shelter movement for battered women, are realizing that women risk losing custody if they seek more (or sometimes any) child support or stability from fathers in terms of visitation. Incredibly, mothers also risk losing custody if they accuse fathers of beating or sexually abusing them or their children—even or especially if these allegations are detailed and supported by experts.

Many judges still believe that “just because a man beats his wife doesn’t mean he’s an unfit father.” While it is true that many children of violent fathers reject violence when they grow up, many do not. Both studies and common sense suggest that a violent, woman-hating father teaches his son to become—and his daughter to marry—a man like himself. Which, despite what some judges say, is not in the best interest of women, children, or society. 1

What about a father who sexually molests his own child? Surely all of us, judges included, take that seriously don’t we? Not necessarily. On the one hand, we vaguely know that 16% of all young American girls (an epidemic number), and a much lower percentage of young American boys, have been sexually molested within the heterosexual family by fathers, grandfathers, uncles, stepfathers, and brothers. Yet when mothers accuse men of sexually abusing children in their families, we don’t believe that they’re telling the truth.

We don’t, of course, want to believe it, but studies document that at least two-thirds of the recent maternal allegations about incest are true, not false, and that neither mothers nor child advocates allege paternal incest more often during a custody battle than at other times. Some fathers’ rights activists, including lawyers and mental health experts, keep insisting that the mothers or children are lying or misguided. And the media continue to cite an increase in “false” maternal allegations.

A Washington, D.C. physician, Dr. Elizabeth Morgan, was jailed for more than two years for hiding her daughter, Hilary, from what she and many experts believed was an incestuous relationship with Hilary’s father. The father has consistently denied any wrongdoing and was never found by any court to have sexually abused his daughter Hilary. Hilary's therapists were convinced that she had been sexually abused and was becoming actively suicidal. However, a Virginia judge did prevent him from seeing Hilary’s half-sister Heather, from a previous marriage, who had also accused him of sexually molesting her. Judge Dixon refused to consider this as relevant to the Morgan case.

Dr. Morgan’s lengthy imprisonment haunted me. Judge Herbert Dixon had made Dr. Morgan an example of what can happen to any mother who defies the law—even to save her own child.

Here’s what I have to say about the Morgan case: Look what can happen to a white. God-fearing, Christian, heterosexual mother who is a physician, whose brother is a Justice Department lawyer, whose fiancé (now husband) is a judge, and whose lawyer is an ex-State Attorney General; look what can happen to an extremely privileged “insider” who decides to make a court case of it. Morgan is an insider in terms of class, color, sexual preference, etc. As a woman, she’s still an outsider. Would a male physician be allowed to sit in jail so long without the old boy network springing into action? Dr. Morgan was freed only by the passage of a special bill approved by Congress and the Senate and signed into law by the President. It states that in the future no judge can imprison a resident of Washington, D.C. for more than 12 months without a trial by jury for specific, stated crimes.

What if Dr. Morgan were a Black, Asian or native-Indian woman with only a high school education? A lesbian and an atheist without a single friend or relative in high places? What if the media thought the case not worth the coverage? Interestingly enough, many of the media and psychiatric reports on Dr. Elizabeth Morgan bore an uncanny resemblance to those of another mother-kidnapper: Mary Beth Whitehead. Both mothers were often described as narcissistic, righteous, stubborn, manipulative, and obsessed “borderline personalities.” This is not surprising. Despite differences in class and education, both were viewed by experts who share the same biased views of women.

There is a danger in focusing exclusively on the incest-custody kidnapping battles. If we finally convince judges that some fathers do sexually abuse their children and that it’s a bad thing to do, then judges might begin to deny custody to incestuous fathers but they’ll tend to view all non-incestuous fathers as automatically worthy of custody—if only by comparison. Still, how can we not focus on some blatant miscarriages of justice?

Marcia Rimland was a woman driven to the edge—and over the edge—by a court system bent on thwarting her ability to protect her four-year-old daughter from harm. When I joined a demonstration called by the Coalition for Family Justice last summer to mourn the deaths of Rimland and her daughter, I was filled with both grief and rage.

It was a childcare worker and Rimland herself who first suspected that Rimland’s estranged husband, Ari Adler, was sexually abusing their daughter, Abigail. Abigail began having tantrums, weeping uncontrollably, and masturbating excessively after visits to her father. After four play-and-talk sessions with Abigail, a clinical social worker validated the child’s probable sexual abuse. But in Rockland County, N.Y. Family Court, the social worker’s findings were challenged. Another sex abuse validator concluded there were problems with the social worker’s findings, including failure to adequately explore the possibility that the child was coached by her mother. However, the second validator never evaluated the child in person.

After this report, Judge William P. Warren decided to reinstate Adler’s overnight, unsupervised visits with Abigail. Marcia Rimland made a hasty appeal to the Appellate Division in Brooklyn, where a stay of Warren’s order was issued—one that allowed supervised visitation by the father in the home of his friends—the very place at which the alleged sexual abuse had continually taken place. Abigail was scheduled to spend three overnight visits and a full weekend with her father before any court would reconsider the issue.

The night before the first mandated visitation, Rimland gave Abigail a tranquilizer. She and the child then sat in a red Toyota with the motor running in an enclosed garage until they both were dead from carbon monoxide inhalation. “I have no choice, I hope you understand,” read Rimland’s suicide note.

Many people will say that the murder-suicide proves that Marcia Rimland was crazy all along. But I believe that we should also view Rimland as a woman driven crazy—driven to despair and desperation. Although her action was personal, not political, we can analyze it politically and try to understand its meaning.

Most research shows us that when mothers or daycare workers allege paternal sexual abuse, it is very likely true. Sometimes, however, one cannot substantiate it fully or clearly enough. This does not mean that the mother has lied or that she is crazy or malevolent. It means that our techniques of eliciting information from children are not advanced enough.

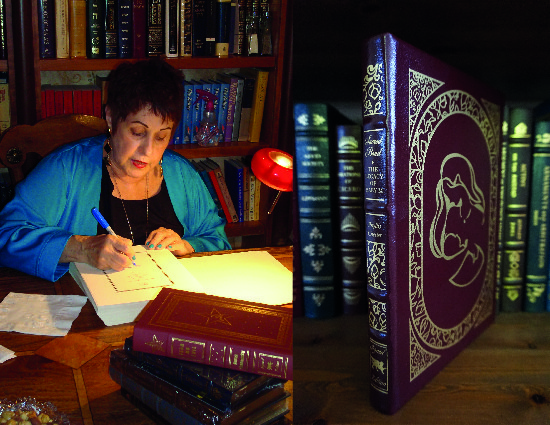

Yet, in the course of writing Mothers on Trial: The Battle for Children and Custody, I found that mothers who allege and can document sexual abuse are increasingly punished by losing custody of the child they are trying to protect. Many lawyers now advise mothers: “If it’s true, don’t allege it, or chances are you are going to lose custody.” It’s hard to convey the extent to which mothers are blamed, disparaged, feared, hated, belittled, and not believed in the American court system.

Marcia Rimland was a matrimonial lawyer; she knew what she was up against. She was distraught beyond measure, perhaps clinically insane. But she was also, objectively, trapped.

Let’s consider why Rimland thought she had “no choice.” Her simplest choice would have been to obey the court and permit her husband overnight visitation with fouryear-old Abigail—an option she viewed as complying with and presiding over the slow destruction of her child.

Like many mothers, Rimland could have watched Abigail slowly come apart. Rimland could have denied what she believed was happening or denied that it was “that bad.” Perhaps Abigail would “only” develop a multiple personality syndrome. Perhaps, like Hillary, Elizabeth Morgan’s child, she would become actively suicidal. Perhaps, like Sherry Neustein in another well-known case, Abigail would develop anorexia nervosa and begin to suffer from malnutrition. Perhaps Abigail would identify with her aggressor, blame her mother for not saving her, and become utterly lost in the fugue state we mistakenly call femininity. Perhaps Abigail would one day become a prostitute. Studies by sociologists and criminal justice researchers show that 80% to 90% of prostitutes have been victims of incest and childhood sexual abuse. If not a prostitute, then somebody clearly with a limited capacity to enjoy a quality life, with low self-esteem and with a good deal of self-hatred.

“The child could have survived it,” some women have said to me, in macho voices. “We know women who have been through incest. What was the matter with Marcia Rimland? Was her kid better than everyone else’s? I got though it, my neighbor’s daughter got through it, we can all get through it. Now there’s even treatment for incest.” Marcia Rimland decided that she would not accept this deal. She could not live if she turned her back on what so many of us learn to live with or minimize, namely, the sexual abuse of children by adult men.

Rimland’s second option was to run away with her child—to go underground. But unlike Elizabeth Morgan, Rimland didn’t have a father who was an ex-CIA operative with the will, know-how, and money to go undercover. Rimland had no living parents. There was nobody she could count on to take custody of the child if she got sent to jail. She had no support. Had she called me, I couldn’t have done a thing for her. There is no “North” for women and children; there is no real underground—no sovereign feminist country for women (or men) in flight from sexual violence. Runaway mothers make it onto television documentaries, but they often lose custody of the kids and go to jail.

A third option: Rimland could have killed the alleged abuser instead of herself and her child. But again, if Rimland shot Adler, who would raise her child? Rimland knew she would probably go to jail for a very long time. This is routinely what happens when battered women kill violent husbands or boyfriends—forget about men they’re no longer living with. There have been some governors granting clemencies in these cases, but it’s very rare.

Anyway, Rimland was probably a “nice” girl, and nice girls don’t shoot men or cut off their penises. Nice girls usually turn their rage inward. They leave the place of unbearable pain by killing themselves, either slowly or suddenly.

So, from her point of view and mine, Rimland had no acceptable options. She was desperate. She knew the score. Like the heroine Sethe in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved, Marcia Rimland saw the slave catchers coming. She heard their breath hard on her heels and she refused to give up her daughter or herself.

Clearly, we need to provide more options for women like Rimland caught in the jaws of an unfeeling legal system. For a start, there should be an independent review of the Rimland-Adler case by judges, mental health professionals, and lawyers outside of Rockland County. Some very obvious, hard questions demand an answer:

Why didn’t Judge Warren listen to the validator’s report that sexual abuse had occurred? This validator interviewed both parents and the child. Why did Warren listen to a report that a second validator issued after not having interviewed anybody, which merely quibbled with the first validator’s methodology? Why did the Appeals Court allow any unsupervised visitation between Adler and his daughter? Why did the D.A. in Rockland County not pursue the first validator’s report of sexual abuse? What sort of political pressure, if any, was put on the judges involved in this case?

At the very least, Judge Warren should have erred on the side of caution. He should have said, “Something is going on. I don’t know what it is. Let’s get more evaluations. Meanwhile, let’s have neutral, trained personnel supervise the visits.” The judge could have at least done that. The appellate level could have done that. I suspect they didn’t because they never believed the mother or the first validator.

As a society, we are in denial about incest and other forms of male violence against women and children. Ironically, even as there are more books, articles, conferences,

and first-hand survivor testimony about incest and molestation of children, it is more difficult for individual mothers to get a fair hearing. There seems to be a need to say, “Well maybe it’s going on somewhere else out there—but not in my courtroom, not on this block, not next door to me, not in my marriage.”

It’s easier for us to blame the victim; to assume the mother is crazy, or exaggerating, or lying, or just being difficult. And a mother overwhelmed by fear that her child is

being abused is not always a model of calm, restrained behavior. She may tremble and stutter in fear and in panic. She may cry or rage. And the judge may unthinkingly choose to believe a smooth, calm, rational—but not necessarily innocent—father.

Deep structural changes. are required to combat the moral insanity that exists in courtrooms and lawyers’ offices. Well-intentioned judges and mental health professionals are

utterly unprepared to deal with allegations of child sexual abuse in any context, no less in the confusion of a custody battle. At best, they are seriously perplexed. In frustration, they “blame the victim” and “pass the buck” on to the next judge.

We must learn to handle child sexual abuse allegations differently: rapidly, very expertly, and with a cadre of specially trained professionals, not witch hunters. The trial and appeal process must be accelerated, and the child—as well as due process—protected at all costs. Psychiatry, psychology, and social work have not acquitted themselves nobly in this area. Therefore, interdisciplinary guidelines must be developed by a coalition of feminist grass-roots workers, scholars, and activists, many of whom are also psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. Such guidelines, or protocols, must be standardized, applied, and enforced everywhere.

While such within-the-system measures are being developed, we must dare to believe and shelter the “protective parent”—most often the mother. Marcia Rimland and her daughter might be alive today if they had had even a temporary escape hatch and some reason to hope for justice.

Some years ago, we began to blame mothers for not leaving men who abuse their children. And mothers began to blame themselves when they discovered many years later that

their daughters had been sexually abused by husbands and fathers. Today, traditional women, who are not necessarily political or feminist, are saying no to sexual violence. They do not want their children to be sexually violated while they stand by and do nothing. They are desperate heroines. We need to make sure they have a way out.

NOTES

1. Two examples among many: Both Marc Lepine, the Montreal mass murderer of 14 young female engineering students, and Colin Thatcher, the wealthy Canadian legislator who for years battered his wife, Joanne Wilson, and then bludgeoned her to death (or perhaps hired someone to do it for him) in the midst of a bitter custody battle, were, as children, humiliated and beaten by their fathers. Both Lepine and Thatcher also observed their fathers physically and verbally abuse their mothers. When boys are brutalized by their fathers, those who become violent often scapegoat women and children and not other men. Thus Lepine didn’t shoot 14 fathers, nor did Thatcher murder—or procure the murder of—another man.