Introduction to Women of the Wall

Jan 01, 2002

Women of the Wall: Claiming Sacred Ground at Judaism's Holy Site

Introduction

By Phyllis Chesler and Rivka Haut

Rabbi Acha said: "The Shekhinah never leaves the Western Wall."

-SHEMOT RABBAH 2

THIS VOLUME IS THE HISTORY OF WOMEN of the Wall, the story of our struggle, at least in its beginning stages. We are a group of Jewish women who have gathered together to pray at the Kotel, the Western Wall in Jerusalem. It is also the story of those who wish to deny us this religious right.

The Women of the Wall have been the subject of countless articles and news reports. Too often, the group has been mischaracterized as Reform, Conservative, political, or as attempting to challenge the rule of Halakhah (Jewish Law) at holy sites in Israel. Many have misrepresented us out of ignorance, not malice. This volume is our way of presenting ourselves to the world as we really are.

Our history began on the morning of December 1, 1988, when a multidenominational group of approximately seventy women approached the Kotel with a Torah scroll to conduct a halakhic women's prayer service. As no provision for Torah reading exists in the women's section, we brought a small folding table with us, upon which to rest the sefer Torah (Torah scroll). We stood together and prayed aloud together; a number of us wore tallitot (prayer shawls). Our service was peaceful until we opened the Torah scroll. Then a woman began yelling. She insisted that women are not permitted to read from a Torah scroll. This alerted some charedi (right-wing fundamentalist) men, who stood on chairs in order to look over the mechitzah (the barrier separating men and women). The men began to loudly curse us. Despite the jeers, curses, and threats of many onlookers, we managed to complete our Torah reading. We were not stopped by the late Rabbi Yehuda Getz, z''l, who was then the Kotel administrator. In fact, a woman who happened to be standing near Rabbi Getz heard him tell the female complainer: "Let them continue. They are not violating Halakhah."

Since that first group service, our struggle has consisted of an attempt to relive that first service; to once again pray together at that holy site, wear tallitot, and read aloud from a Torah scroll. We have endured violence, spent many years in court, and raised many thousands of dollars to this end.

At one point, as a result of intense legal and political pressure to "compromise," we narrowed our vision and limited our demand to be permitted group prayer with a Torah to a mere eleven hours a year, provided that the government would recognize and enforce our right to pray together at the Kotel without our need to further pursue our claim in court. Nevertheless, despite several decisive legal victories, as of this writing we are still not permitted even to stand together and pray aloud as a group at the Kotel.

The story of Women of the Wall is an important chapter in Jewish history. Whether we win our legal battles or not, we have already achieved an important victory. We are a unique example of religious pluralism in action and of Israel-diaspora relationships. The Talmud (Yoma 9b) teaches that when Jews are not united, tragedy results: "In the Second Temple period, people occupied themselves with Torah, mitzvot, and deeds of lovingkindness, so why was it destroyed? Because there was baseless hatred." It was not our foreign enemies who destroyed us, but our incessant internal conflicts. At a time of denomination and political strife, the Women of the Wall are proving that Jews can work and pray together and transcend our differences in a tolerant, even loving, way.

The Torah (Exodus 35:25) teaches that the wise and skilled women of the desert generation wove a cover for the ark, creating a cloth of various hues that blended into a harmonious whole. We view our services as a similar offering to God, utilizing all our talents, all our differing theological views, to create a united service.

It has not been easy for a group composed of educated women, from all religious and ideological streams of Judaism, to form a united prayer group. Serious differences had to be dealt with; compromises had to be made. Our challenge is to remain within the confines of Halakhah, with all its various interpretations, while including those who do not accept Halakhah as binding. We are a work in process. Yet, despite our many and deep philosophical conflicts, we have learned to work together. Remarkably, since our inception no splinter group has emerged. We remain the only women's group presence at the Kotel.

In our view, therefore, our mandate is clear. We represent the Jews of the world who support women's group prayer at the Kotel.

The Jews in the Torah marked their sacred encounters with God with stones. From our earliest history, stones indicated locations of significant encounters with holiness. Jacob marked the place where he dreamed of the angels by erecting a stone monument (Genesis 28:18). Later, he returned to the site and "set up a pillar at the site where God had spoken to him, a pillar of stone" (Genesis 35:14). Even today, when Jews visit cemeteries to pray for the souls of the departed, we leave small stones on top of the engraved headstone. God is sometimes referred to as Tzur, our "Rock" and Redeemer. Rocks signify solidity, timelessness, and eternity and symbolize our relationship to God. So does the Kotel.

The Kotel is a huge wall composed of ancient, massive stones. Some of the newly uncovered stones date from the First Temple period. Most of the stones date from the later Herodian era and are identified by their unique borders. There are tufts of moss and grass growing in the clefts of the stones. People stuff handwritten prayers addressing God into the crevices between the stones. Birds nestle, hover, and flutter among the stones, peering down at the worshippers below.

The Kotel is a surviving remnant of the ancient Temple Mount complex, where the First and Second Temples once stood. The Temple Mount has been considered holy since antiquity, as it is deemed to be the place where the binding of Isaac took place, and also where Muhammed ascended to heaven. The Kotel was not part of the Temple building itself but merely part of the Second Temple's outer retaining wall, built by Herod in the first century B.C.E. Since the destruction of the Second Temple, in 70 C.E., the Kotel replaced the Temple Mount as the most important area for Jewish public prayer. It alone remained, a solidly imposing remnant of Israel's glorious past. The Midrash (Shemot Rabbah 2) teaches that the Shekhinah, God's immanent presence in the world, has never left the Western Wall, but remains there to welcome back the exiled and persecuted Jews. It therefore acquired a special holiness.

There are serious halakhic issues concerning the Temple Mount area. According to many rabbis, Jews today are forbidden to walk upon the actual site where the Temples once stood. In ancient times, and under Jewish law, only people who were ritually pure were permitted upon the Temple Mount. The presence of many mikvaot (ritual baths) close to the Mount attests to the fact that in antiquity these rules were strictly followed. Today, although we do have mikvaot, we lack the other rituals necessary to become ritually pure. Thus, we are halakhically not permitted to stand in that area. However, the exact area where the Temples stood us subject to dispute. The Temple Mount itself has no uncovered remnants of the ancient Temples. Instead, it is now a Muslim prayer area containing two large mosques, al-Aksa and the Dome of the Rock.

For years, under Arab rule, the Kotel was literally a rubble-strewn garbage dump. During the years of Muslim control, Jews were forbidden to pray at the Kotel or allowed to do so only at special times. After the Six Day War, a war of self-defense in 1967, Jews flocked to the newly liberated area. A large plaza was built around the Kotel area, and a mechitzah was erected. The Kotel became a focal point for Jewish worshippers as the most sacred area for Jewish prayer. Jews from all over the world, as well as those in Israel, approach the Kotel to speak to God, to whisper their most personal requests, to place notes to God between the welcoming, ancient stones.

Many public ceremonies take place at the Kotel. Israeli soldiers are sworn in there. Foreign dignitaries are brought there. Bar mitzvah boys receive their first aliyot (being called to the Torah) there. At all hours of the day and night, there are male minyans (prayer quorums) gathered there. On Shabbat and holidays, yeshiva boys approach, singing aloud and dancing, praying together in groups. The Kotel has become the most precious treasure, the heart, of the Israeli state.

In recent times, the entire Temple Mount area, as well as the Kotel, has been the scene of horrific battles. In 1967, in the Six Day War, Israeli soldiers bravely fought through narrow streets, house by house, in hand-to-hand combat, and with many casualties, to redeem the Old City of Jerusalem from centuries of domination by other nations. Many Israeli soldiers died. Miraculously, they succeeded in recapturing Jerusalem for the Jewish people. After two thousand years, Jerusalem was once again part of a sovereign Jewish State. At the heart of the Old City, the Kotel, whose ancient stones were beloved images engraved in Jewish hearts for centuries, awaited the newly returned Jews.

In 1967, the Temple Mount once again became part of the Jewish State. However, under Moshe Dayan's orders, the area was placed under the control of the Muslim council known as the Waqf, which immediately prohibited Jews from praying there and has continued to do so ever since. This exclusion has provoked much opposition. A group known as the Temple Mount Faithful regularly appeals to the Israeli Supreme Court, asking to be permitted to pray atop the Mount on Passover and Tisha B'Av (the day when Jews mourn the destruction of both temples). To date, the Israeli Supreme Court has refused all their pleas, citing the danger of Muslim riots. On Tish B'Av in 2001, this group was once again denied permission to ascend the Temple Mount to pray. However, it was granted permission to have a ceremony in the parking lot outside the Dung Gate, just yards from the ramp leading to the Mount. The ceremony involved a huge stone that the group had designated as the cornerstone for the Third Temple, yet to be built. Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Yisrael Lau denounced the ceremony, which led to Muslim riots on the Mount. Stones were thrown from atop the Temple Mount platform down on worshippers at the Kotel below, and Jews had to be evacuated from the Kotel plaza for almost an hour.

Interestingly, the administrator of the Kotel on this Tisha B'Av expressed dissatisfaction with the fact that Jews worshipping there were evacuated for a while because of stone throwing from above. According to The Jerusalem Post (July 30, 2001), the Kotel administrator Rabbi Shmuel Rabinovitz "blasted the police's decision to evacuate Jews from the Wall during Tisha B'Av, saying that security officials should have been better prepared for Palestinian violence and should have come up with alternatives....This is harmful and painful. It did not have to come to this."

Sadly, the Women of the Wall have been dragged from the Kotel on their previous Tisha B'av observances. Undoubtedly, the State of Israel would have been able to protect the women from charedi attackers and harassers if the administrator in charge had so requested.

Another conflagration arose between Jews and Muslims over the area known as the Western Wall tunnels. In the late years of the twentieth century, Israeli archeologists dug under the Kotel, along the western part that lay buried under the ground. They exposed large, ancient stones, some from the Second Temple, and some dating back even earlier, to the First Temple period. After a few years, the site was opened to supervised tour groups. A highlight of the tour is the opportunity to stand and pray in the spot that is thought to be exactly opposite the site where the Holy of Holies once stood. Prime Minister Ehud Barak decided to open an exit from the tunnels to the Muslim Quarter of the Old City. Up until that point, it had been necessary to retrace one's steps in order to exit the narrow tunnels. The opening of this exist was followed by Arab rioting, and people on both sides were killed. Since then, when a tour group exits the tunnel, it is accompanied by armed Israeli soldiers, in front and behind, protecting people until they return to the Kotel plaza itself.

Another terrible conflict arose on the day before Rosh Hashanah in 2000. Ariel Sharon, not yet prime minister, set off a huge outcry when he asked for and received permission from the Barak government to visit the Temple Mount area. In the aftermath of his visit, what has become known as the al-Aksa intifada broke out; there were riots and demonstrations on the part of Muslim militants, resulting in loss of life. There is strong evidence that the Arab violence was planned long before Sharon's visit. However, this incident marks the beginning of the recent conflict that threatens the safety of the region and the Jewish State.

In 2001, the Temple Mount became the focus of yet another sort of conflict. Archeologists claimed that the Muslim authorities were permitting large-scale construction on the Mount, resulting in the destruction of priceless and irreplaceable antiquities, some dating from First Temple times. The Supreme Court of Israel has been appealed to, but as of this writing the Court has not intervened to stop the destruction. In the United States, a bill has been introduced in Congress to protest this desecration.

In this already embattled zone, we, the Women of the Wall, have precipitated yet another dispute; however, our case is vastly different from the others. Our struggle is not halakhically problematic, nor does it involve other nations, nor does it threaten to cause international trouble. It is the struggle of Jews within Judaism, the struggle of women who wish to claim their rights, as the daughters of Tzelafchad did. It is a battle about which direction the State of Israel will take; it is a struggle for democracy against misogyny.

Let us be clear: Women are certainly able to pray at the Kotel. The women's section, on the right side, is smaller than the men's section. The two are separated by a mechitzah, a barrier about five feet high. The Wall area is always open and always accessible to women. Women may approach the part of the Wall in the women's section, walk right up to the huge stones, touch them, lean upon them, and put notes into their crevices. Women may pray there as individuals and read from siddurim (prayer books). Indeed, women are always praying there, at all hours of the day and night.

However, women cannot engage in the following activities: praying aloud in a group; singing prayers; wearing tallitot (prayer shawls); wearing tefillin (phylacteries); blowing a shofar (ritual ram's horn); carrying or chanting from a sefer Torah (Torah scroll).

These activities are all prohibited to women by Israeli law but not--and this is critically important--by Halakhah. Although women are not obligated to perform such religious acts, under many Orthodox interpretations of Jewish law they are also not prohibited from doing so. In fact, in most modern Orthodox communities throughout the world (e.g., the United States, Israel, England, Canada, Australia, and Sweden), Orthodox women regularly gather in women-only groups in which they perform exactly the same activities that are currently prohibited to women in Israel at the Wall. It is these halakhically permitted activities that we seek to have legalized at the Kotel today.

While we do not oppose the claims of other denominations to pray at the Kotel in their own way, Women of the Wall (WOW) is not challenging the existence of the mechitzah, the barrier that separates men and women. We wish to conduct services in the women's section. Moreover, the group is not constituted as a minyan, which most (though not all) Orthodox rabbis maintain is forbidden to women. The services are non-minyan services, so that all Jewish women, including the strictly Orthodox, may feel comfortable joining the group in prayer.

The initial group service in 1988 left overwhelming impressions on many of the women who participated. Its impact reverberates still.

After that tefillah (prayer service), a group of Israeli women decided to continue, following the model we had set. From the first, they were met with violence. They were cursed, threatened, pushed, shoved, spit upon, and bitten. Heavy metal chairs were thrown at them over the mechitzah. Charedi women tried to pull siddurim out of their hands. Women were physically injured and rushed to hospitals. WOW members--rather than the violent charedim--were arrested by the state. Yet, there was no Israeli law forbidding our prayer services. By the summer of 1989, the Israeli WOW group appealed to the Supreme Court for protection from the serious violence that continuously erupted whenever members prayed together.

The court accepted our case but ordered us to cease and desist from group prayer with a Torah at the Kotel while they considered the matter. WOW thus began its prayer service at the Kotel but conducted the Torah reading at a nearby location.

In 1989, a group of diaspora women who had formed the International Committee for Women of the Wall (ICWOW) decided to raise monies for a Torah scroll to be donated to WOW. The response was extraordinary. Klal Yisrael (Jews) sent small personal checks; so many checks came in that the Torah was purchased very soon. We traveled to Israel in November 1989 with the Torah. With us were many women who had attended the first service. We again attempted to pray with the Torah as we had done in 1988. We were stopped at the security checkpoint and informed that we were forbidden to enter the Kotel plaza with a Torah scroll, and that even without the scroll we could not enter if we wanted to pray together as a group. Indeed, less than two months later, a new regulation was passed by the Ministry of Religion (Kovetz Takanot no. 190) that prohibited our group prayer. Reading from the Torah, wearing a tallit, and praying aloud in a group were all now illegal in the women's section and punishable by a six-month prison term and/or a fine. We chose not to violate this regulation and instead sought justice through legal means. Thus a new lawsuit was born. ICWOW joined with WOW in its attempt to win the legal right to conduct women's halakhic prayer services at the Kotel.

The state's brief against us was shocking. It contained rabbinic accusations that we were "doing the devil's work," "neglecting our husbands and children," "using birth control to avoid having children so that we could spend our time praying in women's minyans." We were also accused of being "misled by feminism."

In 1994, we received a split decision from the Supreme Court. Justice Shlomo Levine ordered that we be permitted to pray as we wished; Justice Menachem Elon, who is also an Orthodox halakhic scholar, wrote a very long opinion in which he upheld the halakhic permissibility of women's prayer groups. However, Elon claimed that conducting such halakhic services at the Kotel "offends the sensibilities of the worshippers" and leads to charedi violence. Instead of condemning the perpetrators of the violence, he condemned us for provoking it. He said that the violence emanates from a very deep place in their hearts. The third judge, Justice Meir Shamgar, wrote that our matter was too weighty for the Supreme Court and required a political solution. Thus, we were sent to a series of Knesset commissions. The Court informed us that "the door would always be open for us to return."

At first, ICWOW and WOW were separate groups with their own attorneys. The Israeli group hired two young and enthusiastic attorneys. The international group turned to Arnold Shpaer, an experienced civil rights attorney who had argued before the Supreme Court many times. WOW's brief argued that women's civil rights were being violated. ICWOW's brief relied heavily upon halakhic material, and, indeed, the Court's decision in 1994 accepted that our practice is halakhic, which is a major victory. However, the decision stopped short of permitting us to actually pray together with police protection; instead, it bounced us into the political arena, where we languished for years, first before the Hollander Commission, then before the Ne'eman Commission.

Years passed with no legal progress. We contemplated engaging in civil disobedience, but ultimately, after much international discussion, both groups reached a consensus to continue our struggle within the courts. In 1995, in response to pressure from many supporters who insisted that we have a feminist attorney, both groups decided to hire one very distinguished attorney: Frances Raday, who conducted the case together with attorneys Jonathan Misheiker and Nira Azriel. ICWOW member Miriam Benson, who is also an attorney, serves as ICWOW's legal liaison with Raday. Our legal team won a unanimous decision in the Supreme Court in May 2000, which declared that Women of the Wall have the right to pray in their manner in the women's section at the Kotel and gave the state six months to enforce their decision. The attorney general requested an additional hearing that, as of this writing, is still pending before nine judges.

Our appeal of the 1994 decision took years. We prepared papers and waited. During this time services continued, and they continue still. The group meets every Rosh Chodesh at 7:00 A.M., at the Kotel. The Torah is brought each time, camouflaged in a portable aron (ark), which is actually a green duffel bag made expressly for this purpose. (How sad that Jewish women, in the State of Israel, must hide a Torah scroll in this way!) The group prays together, sometimes aloud, sometimes in whispers, depending upon the climate and mood of the worshippers there. They sing Hallel, then repair to another location, far from the Kotel but within sight of it, where they unwrap tallitot, tefillin, and the Torah itself, and the service continues.

As we await a decision, our situation has become more complex. In 2000, the Masorati (Conservative) movement decided to accept another site, an extension of the Kotel known as Robinson's Arch, in which to conduct their mixed-gender prayer services without a mechitzah. This group had been attempting to pray in the Kotel plaza, the large open area at a distance from the Kotel where both men and women congregate. They had been seeking a location near the Kotel for egalitarian prayer services and, like us, had been met with violence. The Reform movement, however, has decided to support our struggle by refraining from advancing their own interests at the Kotel at this time.

As for us, we categorically reject any alternative to the Kotel as unacceptable and unnecessary. We pray within the women's section, with women only, and do not require any physical changes or accommodations in that area. We wish to pray together with our sisters, with Klal Yisrael; we do not wish to be isolated in a separate area. Nevertheless, the fact that the Masorati movement negotiated for, and ultimately accepted, another side made us appear unreasonable and unwilling to compromise, in the eyes of the Court. In order to avoid making a decision on the merits of our case, the Court has continually held up the Conservative movement's choice to us as a model of reasonable compromise.

For example, in February 2000, just before issuing their decision, the Supreme Court judges (Eliahu Matza, Dorit Beinish, and Tova Strasburg-Cohen) embarked on an extended tour of the Kotel and surrounding areas. Some of us accompanied them, together with our attorneys. Our first stop was Robinson's arch; archaeologist Einat Mazar explained that this is the only archaeological site in the vicinity of the Temple Mount that remains exactly as it was since the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E. It has not been tampered with in any way. It should remain as is, she stressed; opening this closed area to the public at large as a prayer area would adversely affect it as an archeological site. Mazar pointed out that the Kotel stones cannot be touched at that location, because large boulders, which fell during the destruction and have been allowed to remain exactly where they fell, block physical access to the huge Kotel stones themselves. Moreover, the area is inaccessible to wheelchairs and baby carriages.

The group moved on to Hulda's Gate, and from there to the southeastern corner, where the representative of the Ministry of Religious Affairs pronounced that this was the best site for us. We stood stunned, as the site, besides being extremely difficult to reach, overlooks a cliff and is quite dangerous. "No problem," the representative declared, "we will make it safe and even build a parking lot!" Einat Mazar again intervened and explained that this site was actually used as a Christian burial site; crosses were discovered there. She tried to dissuade the judges from even considering the place. One of the judges, exhausted and panting from the difficult walk, was overheard whispering to another judge that even considering this area was ridiculous, as it was so hard to get to, and mothers and children could not possibly get there.

From there, we all moved to the parking lot near the Kotel plaza. The site is quite far from the Kotel. We stood there aghast, as the area is full of gasoline fumes and is not near the Kotel itself. The state's representative declared this area to be a perfect place for us to pray.

Finally, as we stood in the parking lot, two of our women managed to talk to the Kotel area where the group regularly stands, near the back, far from the men's section, and demonstrated to the judges how and exactly where we pray.

The official tour had ended. We began discussing how we would handle a negative decision.

In May 2000, we were informed that a decision had been reached. To our great surprise, it was a unanimous decision in our favor! We were totally unprepared for this victory. The Court agreed that we have the legal right to pray according to our custom, and it gave the state six months to make the necessary arrangements to guarantee our safety as we exercised our rights. However, despite our (seeming) victory, the end was not yet in sight. Attorney General Elyakim Rubinstein requested an additional hearing. The Court granted his appeal and added six judges to the existing panel. Now nine judges, including Chief Justice Aharon Barak, would hear the appeal.

In June 2001, the nine judges decided that another tour was in order. This time, they visited only Robinson's Arch and the Kotel. This tour took place at high noon on a blistering hot day. Again the Arch was presented by our opponents as the appropriate site for us. As of this writing, and despite an October 31, 2001 hearing on the merits, we still await the judges' decision.

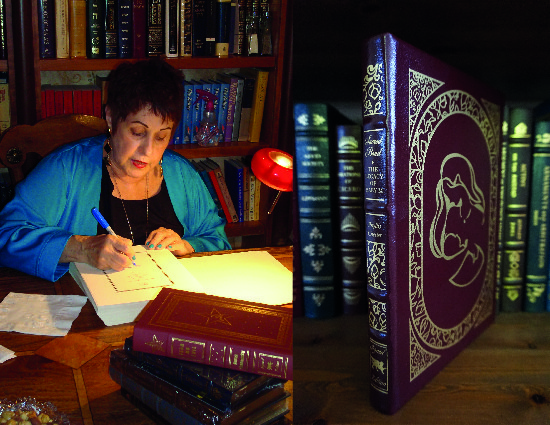

We have experienced high points and low points. The worst incidents were when we were physically attacked and, indeed, some of us were actually dragged away from the Kotel. These incidents can be seen in the photographs included in this volume. More important, some of our high points are also documented here: a bat mitzvah, a female soldier reading from a Torah scroll, lovely moments of prayer. In February 2002, on Rosh Chodesh Adar, we actually experienced what we have longed for--WOW prayed and read from a Torah scroll at the Kotel, before the ancient stones. We have included participants' impressions of this extraordinary prayer service. This was a milestone and a hopeful sign for the future of women's collective prayer at the Kotel.

However, we know that there is much work yet ahead. Many have challenged us. Some have viewed our commitment to Halakhah as old-fashioned and antifeminist. They have been critical of the fact that we follow Orthodox guidelines. Some have opposed the idea that the Kotel deserves the unique importance that has been assigned to it. Some have criticized us for pursuing a feminist agenda when the Jewish State and Jews everywhere are endangered. Always, where women's rights are concerned, women are told to step aside for more important national, military, and economic agendas. Some view our struggle as an attempt by outsiders to transplant Western feminist values into the Israel body politic. We have taken such factors into account and have nevertheless remained steadfast in our decision to forge ahead.

In addition to dealing with the various opponents of women's group prayer, we have challenges within our own ranks. We are two groups separated by a vast distance. Overcoming geographical distance has been an ongoing issue. Half of our board members are Israeli, and half are diaspora women from North America. ICWOW considers itself an auxiliary of WOW. Because WOW conducts services and faces physical danger each time its members pray, it is WOW's right to make certain decisions, because it bears the brunt of the consequences.

Sometimes the two groups have major disagreements. For example, in 1994, after the Court rendered its first decision, a conflict arose. ICWOW believed very strongly that we must appeal the decision; WOW wished to leave the legal arena and focus its efforts on the political and educational spheres. A crisis ensued because we had only fifteen days in which to institute legal proceedings. The deadline was upon us. After much debate, we arranged a transatlantic conference call for about ten women. It was a rather long and very intense call. WOW no longer expected swift legal justice and was frustrated by the constraints placed upon it by the Court. Some members wanted to commit civil disobedience; others wanted to lobby the Knesset and the Israeli public. Everyone was given a chance to speak. Finally, ICWOW convinced WOW to appeal. This meant that WOW would have to "behave" for the duration--no civil disobedience, no illegal activities. To turn to the Court, one must have "clean hands."

Time-zone differences (before widespread Internet access) made instant communication quite difficult. Many Court hearings occurred while diaspora women were asleep, yet ICWOW has always insisted that we be consulted for on-the-spot decisions. ICWOW has spent many sleepless nights worrying about WOW's safety, particularly when violence was threatened. ICWOW members have slept with our phones beside our beds, ready to be awakened in the middle of the night. We have gotten up before dawn to check our phone machines and e-mail about what happened at a WOW 7:00 A.M. service at the Kotel. Although we are far apart geographically, we remain very close.

Over the years, ICWOW has conducted a number of solidarity services across North America to coincide with WOW's prayer services.

Despite the natural strains that arise when two groups are situated so far apart, we have managed to remain a cohesive group, even sharing information about health concerns and family events (births, deaths). When WOW members give birth or adopt children, word goes out over the Internet. When Rivka's late husband was ill, the members of WOW regularly prayed for him. When one of WOW's attorneys, Jonathan Misheiker, lost his son Gilad in an Israeli military helicopter crash, ICWOW shared in the pain. Of course, when ICWOW members visit Israel, they attend WOW's planning sessions as well as visit privately.

WOW has become a community, a feminist sisterhood, and a spiritual home for many of its members. WOW members get together not only to pray once a month, but also to study Torah together. WOW has read aloud from Megillat Esther on Purim and Eikhah on Tish B'av and has been joined by many women. WOW also conducts bat mitzvah ceremonies for Jewish girls at the Kotel. WOW has sponsored seminars, lectures, and retreats. Currently, it is engaged in a major, ongoing campaign to educate Israelis and the world about religious possibilities for Jewish women.

WOW has spoken openly about its struggle to the secular world media. It has also been the subject of several documentaries. ICWOW has been more constrained about how we present our lawsuit in the non-Jewish media.

We have an e-mail list for board members only. Here we discuss issues of Halakhah (e.g., which prayers to say and which to omit, whose halakhic authority to follow), updated legal reports, and other issues thar arise. Reports of the prayer services are also sent over the Internet. One of ICWOW's board members, Rabbi Gail Labovitz, regularly sends out e-mail notices of WOW's prayer schedule and activities to thousands of people from around the world.

We are essentially a grassroots organization, without an office or a paid staff until quite recently, when WOW hired a part-time coordinator.

While ICWOW remains WOW's sister organization, neither group has ever become affiliated with any other organization in the Jewish world, either in the diaspora or in Israel. Our historic prayer service was organized in Jerusalem at an American Jewish Congress service. We have had support from a number of friendly organizations. In the beginning, the New Israel Fund assisted us enormously in financial and organizational ways. The Reform movement assisted us politically in Israel and continues to do so. Many organizations--Artza, Hadassah, National Council for Jewish Women, Rabbinical Assembly, US/Israel Women to Women, Women's League for Conservative Judaism, and the World Jewish Congress--wrote letters to both Knesset commissions on our behalf. Many representatives of these organizations have prayed together with WOW. The Israel Women's Network testified on our behalf before the Sheves Commission. However, despite our concerted efforts, no Jewish organization submitted an amicus brief on our behalf or undertook to legally represent us. No Jewish organization or major philanthropist ever funded us in a major or ongoing way.

Some organizations have awarded us small grants, as have some individuals. On the whole, we have raised funds ourselves in various ways. We have gone on speaking tours, held parlor meetings, sold WOW-related ritual articles. We have struggled to raise large sums for our legal expenses. We have received support from some religious groups, but we have maintained our independence from any specific stream of Judaism. Most of our donations have been from individuals--small amounts, sent in one at a time, in response to newsletter requests.

Our struggle has received enormous grassroots support. When we mention that we are part of Women of the Wall, many Jews literally become radiant with pleasure and pride. For example, in 1989, as we have noted, we decided to raise funds for a Torah scroll to be used by WOW. With little publicity, money flowed in, and we soon had enough to purchase the Torah, a gift from diaspora women and men, to the women of Jerusalem. This is the Torah that is still read by the group. In addition to organizational letters, many individual letters of support were written on our behalf to the Israeli government. Rabbis from every denomination wrote letters of support.

Few Orthodox rabbis or Orthodox women's groups have supported us, but the ones who have are well known and special. Rabbi Rene Sirat, former chief rabbi of France, mentioned us in a speech in which he noted that despite the enormous educational accomplishments of Jewish women in the modern world, at the Kotel they still "cannot hear anything, see anything, or participate in any religious ceremony." Rabbi Sirat called on Jewish men to do teshuvah (repentance) for their behavior toward Jewish women. The late Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, z''l, joined us at the Torah dedication ceremony. Finally, the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance (JOFA) congratulated us in a newspaper ad upon our May 2000 legal victory.

One may ask the following: What cause could unite twenty-five women, radical feminists and Orthodox feminists, lawyers and professors, housewives and mothers. Conservative and Reform women, rabbis and rebbetzins, from different parts of the world? How could they continue, for thirteen years, to endure physical violence, verbal curses, ridicule, accusations of heresy, and setback after setback--not for monetary gain, or personal fame, but for an ideal to which they cling and that they will not abandon? What drives them to spend hours lecturing, educating, raising funds? Why must they pray at that place and not accept a substitute site? Why can't they pray like the other women there; why do they need to pray in groups, with tallit and sefer Torah? Why is this cause so important?

Each writer in this anthology deals with these questions and answers them in her own way.

Some of our members are North Americans who regularly visit Israel. Some are Israelis, including both sabras and Jews who have made Aliyah from other countries such as the United States, Canada, France, England, and Morocco. Some members spent a year or more in Israel, where they became active members of WOW, and then joined ICWOW when they returned to the United States. Some are Israeli and have remained there.

Some of our members have dropped out for various reasons; to our knowledge, no one has ceased being a supporter. Some active board members have no written essays for this anthology. One of us died trying to rescue an Israeli child who was drowning. Her name is Barbara Wachs, z'll. She is in our photographs.

Our contributors are Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist, unaffiliated, and secular. They are rabbis, rebbetzins, politicians, lawyers, professors, scholars, feminist activists, artists, writers, a religious singer, a dance therapist, and a filmmaker.

We, the co-editors of this volume, symbolize the different backgrounds and diversity of beliefs that the group encompasses. We first met at the Kotel, at the first tefillah. Rivka, while organizing the first service, had designated women who would lead prayers and read Torah but had left open some Torah honors, to be given out on the spot. When the time came to uncover the Torah scroll, which had been placed on the folding table we had brought with us, Rivka looked around at the assembled women. One woman caught her eye. Despite the threatening sounds that had begun emanating from over the mechitzah, this woman seemed oblivious to any danger. She seemed to be in another world, focused on what we--and not our opponents--were doing. Her eyes were so dreamy, so happy, so otherworldly. Rivka invited her to open the Torah for us. This was how we first met, at the Kotel, before the Torah.

After the conference, we discovered that we both lived in Brooklyn, New York. Phyllis gave Rivka copies of her books. Rivka took Phyllis to demonstrations on behalf of agunot (women denied religious divorces). Despite major differences in our lifestyles, and after some serious disagreements, we became close friends. Phyllis, a much-traveled radical feminist author and psychologist, is involved in many feminist causes. Rivka, who leads a traditional sheltered Orthodox lifestyle, is involved in Orthodox women's issues, including women's prayer groups. Our collaboration on WOW has led to a real friendship. We have celebrated Jewish holidays together, we have shared sad times, and our families have become friendly. We engage in weekly Torah study together. We hope that this book, our first published work together, will be followed by others.

The Torah teaches that when the Israelites crossed the Reed Sea, they were surrounded by walls: "and the water was a wall for them, on their right side and their left side." We, the writers of this volume, also feel that, since December 1, 1988, our lives have been surrounded by walls. The Western Wall, the Kotel, looms large in our lives, as do the walls of prejudice and discrimination that surround us and threaten to hem us in. Our souls yearn to pray, in peace, in the sacred place, to read from our holy Torah, together with other Jewish women. This volume is the story of our efforts to attain that goal.

It is our hope that after you have read this volume, you will have a greater understanding of Women of the Wall; its history, halakhic underpinnings, legal struggle, and philosophy; and the personal stories of many in the group. The ark in the desert Tabernacle had a cherub placed on each side. Some commentators say they were actually figures of winged children, one male and one female. They faced each other. Their presence in the Tabernacle may have been to teach and remind the people of Israel that both men and women are necessary, and desired, in the worship of God; that both men and women are to be invited into the most innermost precincts of worship, where humanity encounters the Divine. Until and unless this becomes a reality, as long as women are excluded from sacred space, there can be no complete worship of God.