Foreword to Jewish Women Speak Out

Jan 01, 1995

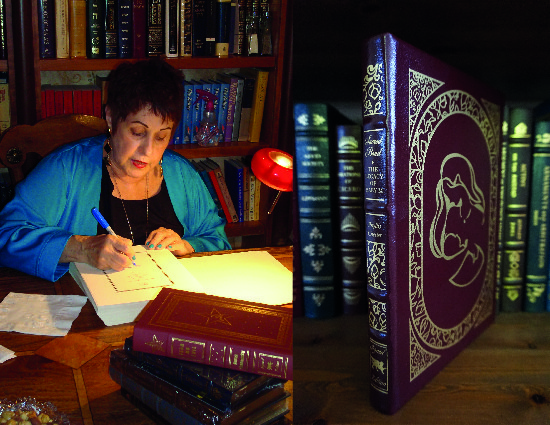

Jewish Women Speak Out: Expanding the Boundaries of Psychology

This is a wonderful anthology, full of wisdom, information, and steady, quiet courage. I warmly welcome it. However, I am also deeply saddened, sobered, by its existence, or rather, by the need for its existence. Jewish Women Speak Out, Expanding The Boundaries of Psychology, edited by Kayla Weiner and Arinna Moon, exists because anti-Semitism still exists. Among educated folk. Among feminist folk. Among feminist therapist folk. Among Jewish feminist therapist folk. In America.

Despite all the progressive movements Jews have joined and led, despite all the Jewish pre- and post-Holocaust attempts to assimilate, to become Jewishly invisible, to understand things from the "other" person's point of view (a la Freud), 55 years after the rise of European Nazism, American Jewish feminists found it necessary to create a Jewish caucus within a feminist, professional organization. This anthology is an outgrowth of their first conference.

The Jewish Caucus is part of the Association for Women in Psychology (AWP), an organization I co-founded in 1969-1970. The Association has endured for more than 25 years, proof, perhaps, of the enduring sexism and hostility towards feminism within the professions, as well as to women's natural/conditioned gravitational pull towards each other.

In 1989, some Jewish members of AWP formed a Jewish caucus. Perhaps the increased feminist awareness of the importance of ritual, or the feminist reclamation of "sacred space" within Judaism, compelled Jewish AWP members to do so; perhaps the increase in anti-Semitism which always accompanies the rise of fundamentalism in history, also spurred them on. Whatever explanation applies, I'm glad they exist, and I'm glad they're publishing this collection. Sadly, though, Jewish Women Speak Out proves how little has changed since I first encountered anti-Semitism among radical feminists and lesbians in the early 1970's.

That encounter sent me straight to Israel for the first time a few months after Women and Madness was first published in 1972. I remember browsing in a Tel Aviv shop and unexpectedly coming upon Time magazine's review of the book in January of 1973. At the time, I was shocked more by the blatantly anti-Semitic illustration that accompanied the review than by the anti-feminist review itself. Freud was caricatured as a big-nosed, ugly, pygmy-midget, clearly "in lust" with the tall, blonde, Viking princess on his couch. The pure racism just leapt off the page. In 1982, in Vienna, I visited the Freud Museum; they closed it, briefly, so that I could be there quietly. I lay down on that famous, faded red couch of his, and I let Freud tell me all his problems! Sigmund moved me, he talked to me: Jew to Jew.

When I returned to America, I started wearing big Jewish stars to the most radical rallies--my version of an Afro, or a dashiki. I waited for someone to challenge me, publicly, on The Jewish Question. Few ever did. More often, that took place behind closed, sometimes behind my back. I was either accused of being the wrong kind of Jew (too pushy, too verbal, too visible, too sexy, too smart), or a too-typical kind of Jew (reactionary, racist, capitalist, imperialist, sectarian). In short, I was sometimes viewed as a betrayer of feminism because I dared to identify anti-Semitism as racism, and to therefore identify myself both as a Jew and as a Zionist.

Between 1973 and 1975, I tried, but failed, to interest the other Jewish feminists in meeting, on a continuous basis, to discuss the problem of anti-Semitism. At the time, one rising feminist light said: "Phyllis, it may be a problem, but it's not my problem." Another said that "she didn't identify as a Jew anyway--and hoped I'd give it up too." (Within a decade, both women would have important things to say on this very subject, and would even become quite successful as "professional" Jewish feminists.)

I began to hear stories from other feminists about their experiences of anti-Semitism within the movement. (Of course, the stories of sexism, racism, homophobia within the Jewish and Israeli communities, never stopped coming my way either). As a radical feminist I didn't know what to do. I felt it was important to act on my analysis of anti-Semitism. I feared that to do so would irreparably slow us down in terms of feminist progress. I was right on both counts. Within a few years, other Jewish feminist began to talk about the "Problem that dared not speak its name." In 1975-1976, I participated in the first National Jewish Feminist Conference, which took place at the McAlpin hotel in New York City. It was a thrilling and energizing conference.

I remember spending hours with Aviva Cantor, who, together with Susan Weidman Schneider, founded Lilith magazine in 1976. Lilith published my conversation with Aviva in the winter of 1976/77. Although I'd been quoted at length on my feminism and Judaism at the McAlpin Hotel conference, this was really my first "out" interview as a Jew and a Zionist. When my friend Naomi Weisstein, also a co-founder of AWP, published her paper "Woman as Nigger," I told her, "Try 'Woman as Jew'" because that would take us back 5,000 years of being without land, in exile, without any means of self-defense or economic independence.

As a feminist, I was also learning from Jewish and Israeli history. I began to think about the importance of feminist sovereign space, of a feminist government in exile. I had in mind something far beyond a coffee house, magazine, shelter for battered women, or Women's Studies program. I was thinking about the creation of feminist sovereign space psychologically, legally, economically and militarily.

I told Aviva that feminists would have to learn how to fly planes, use and control technology, defend ourselves and each other, i.e., to do all the things that men do. Dreamer that I am, I said that I believed a feminist government would be the only solution to The Woman Problem. Not just in one little territory, but world-wide, everywhere. Incredulous, Aviva asked me: "But is it possible?" And I, Jewish-style, answered a question with a question. "Do you think the State of Israel seemed possible, in say, 1820?" "No," said Aviva. "Well," said I, "I learned from the State of Israel that the impossible is possible."

In 1975, together with New York Jewish feminists Esther Broner, Edith Issac-Rose, Bea Kreloff, Letty Cottin Pogrebin and Lily Rivlin, we began to hold feminist seders. With feminist pride, and love, many of our members wrote about us; Lily made a wonderful and inspiring film about us. We were enormously privileged. History--and our own unaffiliated, grassroots nature--allowed us to be radically Jewish and feminist with each other, at no cost. All gain, no pain. Our venture was both splendid and flawed. We had more media coverage than sisterhood, more celebrities per square inch than Yiddishkeit. We were the keepers of the flame of our own growing myth. Sadly, we had no "hands-on" connection to other, similar grassroots groups, around the country or around the world. We never managed to include sons as well as daughters, we had little institutional influence, and we did not collectively create an evolving Haggadah, complete with specific rituals. (We were so creative, so madcap, that each year we dared to have different rituals, and to focus on different themes.) Lily Rivlin, Esther Broner and myself, also created Jewish feminist New Year's and Yom Kippur rituals, as well as rituals for other rites of passage, such as giving birth, having a hysterectomy, losing a loved one, etc.

In 1980, I attended the Conference on Women in Copenhagen sponsored by the United Nations. In Copenhagen, Israel officially became the "Jew of the world", the scapegoat for the West, the cause of every country's plagues. It was not a conference about or for women; it was really a conference about Palestinian and other so-called Third World rights. I heard women, most of whom had been trained by Russia, and/or who were members of their own countries' ruling-class elite, thunder, chant, repeat, over and over again: "Our problems--drought, famine, tyranny--are due to Apartheid in South Africa and Zionism." The anti-Semitism, masquerading as anti-Zionism, was truly staggering. More important, I saw what absolute pushovers other, presumably "pushy Jewish women" were, when confronted with shouted hatred, oft-told lies, propaganda.

In 1980-81, I did three things: I persuaded the Israeli government to allow me to organize a really radical feminist conference and hold it in Jerusalem; I wrote about the Copenhagen Conference for Lilith, but under a pseudonym, so as to not jeopardize the safety of feminists from Arab and Islamic countries whom I was inviting, to this conference-that-never-was; and I coordinated a panel on Feminism and Anti-Semitism for the National Women's Studies Association meeting in Storrs, Connecticut. I did so, because I did not want to talk about anti-Semitism among feminists alone, or behind closed doors. I wanted to present the facts publicly, to other American feminists.

I remember "coming out" again, as a Zionist, at this panel. I talked about Zionism as the national liberation movement of the Jewish people. I described how feminist reports of anti-Semitism in our ranks were often seen as exaggerated, groundless, lies. I loved this group of women. I said: "If we understand why women need separate shelters for battered women, coffee houses, music festivals, land trusts, Women's Studies programs, can't we also understand why Jews might need a Jewish state?"

I asked my assembled feminist sisters: "Who'd hide me and all the other Jewish feminists and our families in their attics when the Nazis come to get us?" "I will, I will," promised an earnestly distraught Susan Griffen. Some Christian and Jewish feminists were not at all amused; some women of color were a lot less than amused. From 1981-1990, I would have many passionate conversations with individual Christian feminists, both white, and of color, who emotionally seemed to believe that 20th century Jews and Zionists were more responsible than anyone else for the death of the Goddess two to three more thousand years ago and for the slave-trade four centuries ago; that Zionism was responsible for racism in America today--and for all forms of American and Western imperialism; that all Jews are rich, powerful, racists, etc.

Mainly, many feminists truly believed that Jewish women, most of whom were white-skinned were, unjustifiably, trying to jump on, profit from, even halt feminist, revolutionary, progress against racism, imperialism, or colonialism, and to "ruin it" for women of color. Worldwide, they were no more accepted among their African, Hispanic and Asian brothers than we were, among our Jewish brothers, but like the rest of us, they found it easier to fight with other women than to take on the brothers.

Post-Storrs, I turned over panel tapes to Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who incorporated some of the information into her important article on anti-Sarmatism among feminists. The article, which appeared in Ms magazine in 1982, caused quite a stir. A number of feminists asked me, privately, whether I thought Letty was exaggerating, grandstanding, merely applying for a position in the Jewish establishment, etc. I told them she was neither exaggerating nor grandstanding, and might only be forced to apply for a "position" as a feminist among Jews if the career-path was too heartbreaking for her as a Jew among feminists.

In 1988, I was one of the women who davenned for the first time ever at the Kotel in Jerusalem with a Torah. In fact, I had the great honor of opening the Torah for the women that morning on December 1, 1988. It wedded me to the action. I helped form the International Committee for Women at the Kotel, and became a name-plaintiff in the historic lawsuit on behalf of Jewish women's religious rights. After seven years the matter is still pending. The suit was heard by the Israeli Supreme Court and deserves a separate article entirely. I often tell people that what we did was the equivalent of Catholic women taking over the Vatican and officiating at Mass; and that I believed that women's mental health would vastly improve, as a result of actions like this.

In the beginning, many Jewish and Israeli feminists, secularists, and radicals, tried to pry me loose from what they saw as an unimportant, or even reactionary struggle. Didn't I see that we were arguing for a piece of a tainted pie, that we were settling for too little, and for the wrong thing? They had a point--but they were also wrong. Women have as much right as men do to exercise our rights as Jews--even if, from the feminist point of view, all patriarchal religions need to be transformed/overthrown. In the course of this struggle I have seen how a moderate, liberal, demand for women's civil and human rights, is treated as if it's a revolutionary demand. Which, in a sense makes it revolutionary.

I will top here. There's more, but this is enough. My point is this: that given this history, imagine how moved, angered, saddened, validated I felt when I read what Evelyn Torton Beck has to say about the "resistance to including Jews in the developing field of multicultural psychology," and about the numerous "unacknowledged acts of anti-Semitic complicity on the part of lesbian feminists." Beck describes numerous instances of blatant anti-Semitism in the published works of psychoanalysts, most notably, Thomas Szasz and M. Masud R. Khan, which have gone unchallenged. (I guess once you've read about Carl Gustav Jung's profound and virulent anti-Semitism, there's really no cause for surprise, is there? And yet one is still always a little surprised). Beck also describes how difficult it still is to call others on their anti-Semitism--at least, not without risking hostility and failure.

The collection is rich, very rich, and contains unique and creative suggestions about Jewish experience, both sacred and secular, and has implications for Jewish psychological suffering, clinical theory and practice. I could go on, but here's the anthology itself, waiting to be read. Please do so. Use it, dialogue with it, challenge it, embrace it, dance with it, keep it by your bedside, add to it.

To the editors and the contributors: Yasher Koach!